RECORD OF A VENEZUELAN PARIAH

VIII: THE POST-COLLAPSE

We buried my mom on April 2 after a modest funeral and burial. Thanks to the help of a cousin who was staying with us at the time, we found paperwork from my late aunt who purchased two burial plots next to the ones where my grandmother and uncle’s remains are at. She passed away in 2015 on the same week my mom started her chemo.

During her final days, my mom left me and my brother with one final command: “Never fight between yourselves, look at what happened to your uncles.” From 2005, and most notably from 2009 onwards, she had to witness how her two remaining living brothers waged a war against each other over control of their business.

That fight consumed them in such a way that they could never reconcile in life after one of them passed in 2015. In the end, that which they fought over for doesn’t even exist anymore, all that’s left.

My brother and I live under that rule without fail, working as a team of severely flawed and socially inept adults, but taking care of each other.

I had a Novena organized for my mom at the Saint Peter Church in Caracas’ eponymous parish, where we used to live. Some of her friends went, including people who worked for her at the hospital for 16 years. One such doctor, Psychiatrist Dr. Vielma, was weeks away from leaving Venezuela towards Chile just like many doctors and professionals have done to flee from socialism and in search of a better life.

She had a practice at a nearby private clinic where my mom also worked as an anesthesiologist in addition to her work at the hospital. Although she was closing shop and not taking in new patients, she offered free consultations to me and my brother while she was still in the country, because, suffice to say, we were devastated.

I started to feel ill halfway through the Novena days, I attributed it to exhaustion and sleep deprivation, since it had been years since I had last slept well, something that worsened as my mom’s health began to decline — but it turns out that I never got chickenpox and a kid, and let me tell you, getting it at the age of 30 is not what I’d like a pleasant experience.

I couldn’t go to the last five days of the Novena. The rest of that week was one of the worst times of my life. My body was wrecked by chickenpox, high fever, pain all over, and nasty blisters and scabs. My mind was shattered, I hated myself for failing to save her, for not being resourceful enough to find a way to get her out of the country and proper treatment. I didn’t want to talk to my dad, who belligerently started berating me for finding out that your mom had cancer and died through someone else.”

And then, on that Saturday, my dad unceremoniously revealed through me via Google Chat (a messaging platform that I don’t think anyone uses anymore) that I’m not actually his first born because he had an affair with a woman in Maracaibo back when he was going to med school. Unlike me who had no education, he made sure to emphasize that this firstborn was a summa cum laude psychologist graduate and so was his wife — in other words: he has his life in order and you don’t.

I have no idea how I didn’t completely go insane that week since I was mentally devastated, my body laid waste by chickenpox, and now that revelation — oh, there was also a blackout in my area that extended all the way past the next morning, because of course.

If I’m completely honest with you, I managed to track the guy based on what little info my dad disclosed, but I have never talked to him. Later I would then find out that my father keeps his siblings compartmentalized, with me and my brother being the “outcast” group, and his other offspring composing another group. I have nothing against them, but it’s just one of those things in my life that I don’t know how to proceed with.

Some of my cousins helped cook for my brother during those days that I was sick, but I barely wanted or could stomach anything. It wasn’t until that following Sunday where I felt better-ish enough to eat most of an arepa. I spent the following days at a blank, just responding to messages, and mustering enough energy and willpower to clean the fridge. The last pasta I had reheated for my mom was still there, a few vials of erythropoietin, and a bunch other stuff.

It took about 19 days for me to feel better enough to go out and drive. I took my brother to a restaurant we used to frequent with my mom back in 2008. I paid over 3 million bolivars for two pizzas and a few drinks — that amount was no longer worth $75 like back in November, when I was almost arrested for “money laundering.” I’d say that by then, it barely amounted to $25, probably less, just to give you an idea of how rapidly a currency can devalue under hyperinflation.

Such was my luck, though, the Maduro regime decided to intervene in that bank on that precise afternoon, disabling its debit cards. I had to wire transfer to the restaurant for the meal using someone else’s phone because mine was barely functional. When we were almost back home I noticed a bread line in a nearby bakery, which meant that there was bread there at last. So I wrapped up that afternoon waiting in line for naught, as my debit card wasn’t working.

I would find out later that the socialist officials had “intervened” in the bank because of a “foreign currency laundering” probe. Ironically, just what their staff had accused me of a few months prior.

The chemotherapy pills that my mom only used for a bit before dying, it turns out they were extremely pricey, I’m talking a couple thousand dollars for a bottle, and I had been given a box with four. Now I could’ve made it like a bandit and I perhaps that would’ve been enough money to illegally smuggle me and my brother out of the country, but those pills were smuggled for my mom, and that’s now how I was raised.

Ultimately, I waited for the same doctor that gave them to us in the first place to track down a cancer patient that specifically needed those pills, and I returned them. I never knew the person’s name other than it was a man, all I could do is hope that the pills helped him in his fight against cancer.

I also hate the pending matter of returning the wheelchair that was borrowed to my mom. That wheelchair was in good shape, and had a tiny metal plate that identified is as hospital property, specifically, cardiology, which is where a friend of my mom took it from in the first place.

As instructed, I took the wheelchair to the hospital, using the still-functional doctors’ reserved parking spot access key to sneak it in. During those days, my mom had told me to “leave one of my white coats on the seat,” a sort of code against theft in that hospital.

I dedicated the next days to try to figure out and scope just how much paperwork I now had done after my mom passed away, like transferring bills to my name, see what pending stuff we may have missed, and most importantly, trying to retrieve her medical degrees and the mountainload of paperwork she had in the process of stamping and legalizing to be able to work as a doctor abroad — because she always had hope that she’d beat cancer and we’d be able to continue with our journey to flee from the country.

Venezuela’s eternal bureaucracy, now severely overloaded by the sheer amount of people trying to get their papers in order to migrate, led to a massive backlog whose only way to overcome was to pay people to “expedite” your requests, if you know what I mean. My mom had enlisted such services, and now I had traced who had what based on her phone messages. I do believe I managed to retrieve all of it, or the main stuff at least.

The cable TV bill was the easiest to switch, and I wish the rest would’ve been as easy. It’s not like there was any money left on her bank accounts, so I didn’t even bother with those legal proceedings. Some stuff I just couldn’t resolve until years later, such as the matter of the state certificate for her apartment so me and my brother would each have half of it. The problem is that although she and other of our neighbors paid their mortgages fully, the office that handled it was dissolved and cannibalized by the Venezuelan state, who appears to have misplaced all records, leaving the apartment in a legal limbo.

I took my brother to Dr. Vielma, and he slowly improved a little because he was completely absorbed into his own little world, more than usual. She eventually ran out of time, as her flight was impending, so we said our goodbyes.

Maduro, who under “normal” circumstances would be up for reelection at the end of 2018, held a highly fraudulent election in May 2018. He banned the opposition from participating, and only allowed “rivals” to participate, with his main contender being a former Chavista governor. He “won,” the international community and local politicians condemned him, but he continued as if nothing had happened.

The inflation had become just so absurdly high that Maduro ordered to “reboot” the Venezuelan bolivar just like Chávez had done in 2008. Instead of three zeroes like back then, this time a whopping five zeroes were axed off the scale. This new iteration of the Bolivar, named the “Sovereign Bolivar” , would go into circulation in August 2018.

Unlike the 2008 reboot, though, there was no oil bonanza to back this new currency, and nothing, absolutely nothing, had been done with regards to fixing the socialist policies and maladies that caused the inflation in the first place. The only meaningful policy reversal that they did at the time was to revoke the provisions that made it illegal to hold or trade in foreign currency.

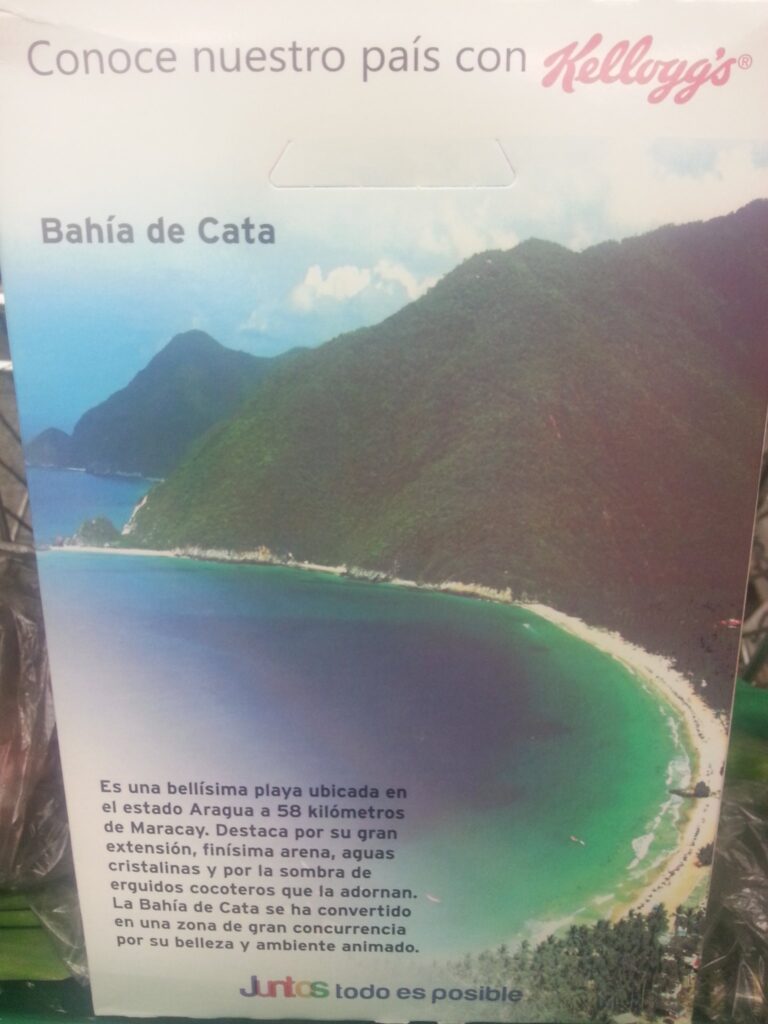

The ruling socialists continued being socialist, though. They seized the infrastructure, assets, and intellectual property of American company Kellogg’s after they decided to leave the country. To this day, any Corn Flakes, Fruit Loops, and other Kellogg’s products that you see in Venezuela are actually made by the Venezuelan regime wearing its skin.

In the absence of regular and known brands such as Colgate toothpaste or Heads & Shoulder shampoo, it was common to see bootleg brands such as “Colgane” and “Hoed & Shouders.” Some of these were distributed through CLAP kits by the regime — so it’s safe to say that someone cut a nice deal and pocketed money by importing dubious quality items for the state.

One of the two worst shortages and/or waiting in line for some moments that I can remember from those last months of 2018 was back in between August or September of that year, when I went to a pharmacy to wait in line for bar soap. After almost two hours I was able to purchase about three or so off-brand soap for “girls.” Soap is soap, and you couldn’t get picky with what you found. While I had soap to shower with, it’d leave you with this rather overwhelming bubblegum scent on your skin.

Another disastrous day took place some weeks later at a store named “Obsession.” This store, located near my old place, specializes in toiletries and beauty and personal care items, but it also had small sections for house cleaning and an even smaller groceries section.

My mom used to frequent that store in its heyday due to its proximity to the clinic she worked at, but also because the prices were rather affordable. I went there one late 2018 morning in search of shampoo for me and my brother. The Bolivarian National Guard was “supervising” the locale, and kept the absurdly long line organized.

Regime officials, clad in the typical socialist red uniforms, were “fiscalizing” the store to make sure that they weren’t “speculating” against the people. To make sure that there were enough supplies to sell to everyone, they had the “brilliant” idea of limiting purchases to two items per person regardless of what you were buying. You needed shampoo, soap, and a bottle of water? Too bad, pick two and two only.

By the time I made it to the store they ran out of shampoo and other stuff, so they further limited purchases to one item per person. So as to justify all the time of my life I had already wasted that morning, I stood on the line, and eventually made it out with a small bottle containing some sort of shady “pre-wash” solution meant to be used on hair salons. I poured half of it on an empty shampoo bottle, and “stretched” both halves by diluting them with some water.

Situations like that, where even finding something to do basic hygiene on yourself, was an uphill, time-consuming endeavor. When I was not living the socialist experience, I was either trying to solve paperwork nuances, taking care of my brother, trying to work on my passion project, and trying to distract my mind with stuff while me and some of my friends trying to find a way for us to legally migrate, always finding some legal hurdle or financial cost impossible to overcome.

Those months, after the reality of my mom’s death began to “settle in,” so to speak, is when the sheer extent of Venezuela’s deterioration began to kick in my head. That was my life, I guess: a constant race to burn through bolivars before their value further dilutes, a new bread line, putting my right thumb on a scanner so the system validates my weekly ration of rice. Waiting for my “meat dealer,” as I’d eloquently refer to it on social media, to bring me my clandestine order of ground beef and chicken breast.

Waiting for two hours of water per day: one in the morning, one at night, the absurdity that is socialist price controls causing two bell peppers and three onions to cost more than my power and cable bill combined. Rerouting my air conditioner’s drain pipe so it discharged on a bucket so that I’d half a “self-rechargable” bucket to flush my toilet. Wire transfers to pay for drinkable water.

That following perhaps, led to me doing some good in this world during a restless May 2018 night. Those were the days where I’d just couldn’t conciliate sleep at night, and more often than not I’d fall asleep only after the sun was out. One such night, I tried to sleep a bit earlier than usual, and turned off all my stuff, left my phone on silent mode, and called it a day.

My antics on social media and content on my website had accrued me a decent following online. Many of them, friends and strangers alike, their words of support and encouragement, they really, really helped me find the strength to keep going. I had a promise to fulfill to my mom, that I’d take care of Christopher, and I’d build a better life for him.

I couldn’t sleep, and the flashing screen on my phone wasn’t helping. I got out of bed and checked on my phone to see messages from a follower who I was not acquainted with. He was a young man from Chile, in an apparent state of inebriation, telling me to not give up and to keep fighting against the “commies,” because he was about to end his life because his life situation was unbearable.

Whatever modicum of sleepiness I had instantly vanished. I spent the rest of that midnight successfully talking him out of it. I’d keep an eye on him whenever possible, and he eventually enrolled in college, or so he told me. Some months later he cut off contact, but not before going on an expletive-laced tirade against the world.

I didn’t hear from him until late 2023. He apologized to me over that outburst, which he honestly didn’t need to. What was important, though, is that he told me his life was much better those days. I hope he’s doing even better these days, whenever he may be at.

That Christmas season was not the bleakest, but definitely the numbest. I felt nothing, the music did nothing, the food was tasteless. My mom was the embodiment of Christmas joy in the house, and she was gone. I didn’t even put decorations that year, and instead of the insignia Venezuelan Christmas ensemble dish: Hallaca, Pan de jamon, and Pernil, I just made a simple pasta dish and called it a day.

And then along came 2019, and the start of a new, intense period in Venezuela.

Maduro’s 2013-2018 term, the one he obtained after “winning” in the 2013 snap election, was days away from ending. Don’t forget that he had just “won” the fraudulent 2018 election, so he was getting ready to begin a new six-year term.

Since the election was neither free, fair, and absolutely not legitimate by any measurement, this effectively meant that if he’d continue in power past January 10, 2019, he would be usurping power as per our constitution states.

The Venezuelan National Assembly, still controlled by the opposition but effectively castrated by the socialist-controlled Supreme Court, who rendered all of its acts null and void, acted upon in accordance to what the constitution says one should do in cases such as what Maduro did, and thus appointed Juan Guaidó, at the time the head of the parliament, as Venezuela’s legitimate interim president.

And thus the stage was set, and lines were drawn.

The United States, Canada, and many other countries recognized Guaidó’s legitimate presidency and denounced Maduro’s illegitimate usurpation. The regime’s allies, such as China, Russia, Cuba, Iran, and other leftist led nations — especially those that had sold their metaphorical soul for oil back in the day — sided with Maduro.

What followed was an intense period of nationwide protests, more regime repression, censorship, international condemnation, and widespread turmoil. Guaidó and the opposition rallied under the banner of three promises that never came to pass: The end of Maduro’s usurpation of power, a transitory government, and free elections.

Whatever goodwill I had left in me with regards to the opposition vanished in 2017 after they essentially sold out the protesters and quelled the protests at the most crucial time of that cycle. Always keep in mind that Venezuela’s mainstream opposition and “opposition” is largely composed of leftist and center-left parties, and the most “right wing” of them is center-right at best.

Still, I was cautiously optimistic, but the problem is that I had seen this tale back in 2017, in 2014, 2013, 2007, 2004, and in 2002 — a recurring cycle encompassing more than half of my life. While there were a couple new faces this time around, the core of the opposition was still the same people I had seen on television ever since I was a kid. I gave them the benefit of the doubt, aware that there are almost two decades’ worth of disappointing precedents.

Others differed, and were highly hopeful that 2019 was going to be it, the year when the socialist nightmare would end — who am I to crush their hopes? I had already lost my mom, most of my sanity, and I made a promise. My priority remained, and still remains, my brother.

In February, Venezuela’s conflict further escalated, with events that took place at the border with Colombia. The socialist regime shutdown the main bridge connecting us with our immediate neighbors, welding shut containers on the road. At the time, international groups organized a “Venezuela live aid” concert with the supposed intention to raise funds to help in Venezuela’s worsening humanitarian crisis. Similarly, a shipment of humanitarian aid was blocked and assaulted by the socialist regime, who refused to let the trucks pass. The same could be said about the supposed “aid” money, who knows who pocketed that in the end.

The Maduro regime “countered” the Live Aid concert, which took place at the Colombian side of the border, with a pro-regime concert on the Venezuelan side. With most embassies now shut down, and no resume worthy enough of a legal work visa of any kind (not to mention my brother’s case), I began to get rather desperate.

I further fell into a deep despair during those days due to a series of upcoming changes in the platforms and methods that I used to secure and move funds around that could’ve potentially led me without access to the savings I had accrued at the time thanks to the help of friends and strangers, effectively stranding me in Venezuela without money to buy food. I wasn’t in a good place due to the overwhelming anxiety and stress it all caused — the only time I had been that bad was during the days my mom was dying.

After weighting my options with regards to legally escaping Venezuela, I swallowed my pride and made peace with my father, an Italian national. After a lengthy one-on-one phone conversation, we put aside nearly 20 years of hostilities and started anew. Although he said he was willing to help us get Italian nationality by right of blood, he insisted that it was not possible due to a slight change in my grandparents’ surname done by Venezuelan migration officials in the 1950s when they arrived on a boat (they mistyped Caruso with Caruzo).

One letter that supposedly prevented me from having dual citizenship (spoilers: it was a lie). Nevertheless, he said he’d look into the matter. In the meantime, I had to either get a new Venezuelan passport or get an extension, as the one I got in 2014 was about to expire (passports had a five-year duration at the time).

Getting a new Venezuelan passport was an odyssey back then, it still is in some ways. You see, it’s not that the Maduro regime didn’t prevent you from leaving (Colombian border shutdown aside) like other socialist/communist regimes had done in the past, it’s just that they made getting passports and other documentation so extremely hard that it served as a “Berlin wall” if you wanna call it like that.

Think of it, they had to, and still do, maintain the facade that they’re a “democratic government.” Preventing people from freely leaving ala Cuba or North Korea would defeat that narrative, right? So they instead built up that metaphorical bureaucratic “wall” to keep people in, or at the very least, slow down the outbound flow.

At the time, you needed to pay for the passport fees through an headache-induicing website that was down more often than it was up. Worst of all, you had to pay using a credit card with a sufficient limit in bolivars to cover the cost. I solved this hurdle through the help of a friend of a friend of mom, who let me use her credit card to pay for a two-year renewal of my passport.

While February was intense, things began to rapidly “cool down” by early March, and it seemed like the fight against the regime had reached yet another standstill, since all the regime had to do was to do the same thing they had been doing on every protest cycle: just wait it out.

And then, when all of us in the country least expected it, Venezuela’s power grid completely collapsed on Thursday, March 7, leaving the entire country without power for several days.

Running water had made its habitual brief return on that morning, and I had some laundry to do. I was also working on a few things on my computer, such as a new post on my blog, a few memes, and seeing if I could work a little more on my passion project. I did have one rather “important” albeit personal appointment on my agenda for later that night: the release of Devil May Cry 5, a game from one of my most liked franchises, and which I had been waiting for so long.

When power went off, I thought it’d be just another “regular” blackout, the ones that lasted a couple hours at worst. Little did I know at the time that we’d go an entire weekend without power. The first sign that the blackout wasn’t a normal one was the fact that cellphones completely signal about an hour into the blackout.

My immediate concern was the frozen food we had in the fridge, so I told my brother that, under no circumstance, we were to open the fridge to keep things for as long as possible.

My brother and I felt disconnected from the rest of the world — and we were quite figuratively so. For all we knew, the end of times could’ve been upon us and we had no way to be informed of what was going on in the country and the rest of the world for that matter. My brother stayed in my room for a while and we talked for a bit. He was quite anxious about everything but he managed to calm down a little, myself as well in the process. He then went to his bedroom and tried to rest.

That night was an extremely disorienting one for me, because even though blackouts weren’t a foreign concept to us, you’d at least hear the sounds of vehicles either passing through that street or nearby ones, and if the outage was just in the area, you could at least see some lights on the horizon through the window of my bedroom.

But that night? Nothing, no cars, no lights, just an absolute pitch black and a deafening silence. You don’t realize just how used you can become to background noise when it’s gone; you either have the sound of a fan, air conditioner, and maybe some tiny lights or indicators in your bedroom to some extent. But to open my eyes, close them, and experience the same darkness regardless disoriented me.

The city was dead and everyone in my vicinity was locked tight in their respective apartments.

Running water had briefly returned that Thursday morning, and although the building’s tanks were full, there was no power for the last working pump in the building to send water from the lower tank to the upper one. So we had to ration the smaller upper tank because my neighbors had no way to pump water upwards across nine floors.

With my evening plans ruined by the blackout, I managed to entertain myself by doing some work on my laptop until I had to cannibalize what was left of its battery in order to charge our phones a little. The trick was to leave the laptop in sleep mode and then plug the phone, which would draw power from the laptop’s battery.

The next morning I woke up very early and most worried about the few beef and chicken that we had stored in our refrigerator, thankfully it was all still frozen. Our kitchen doesn’t get much natural light but I managed to cook an arepa for my brother, I may have added too little salt to the mix though.

Without water we weren’t able to take a shower the day before, and I certainly wanted to take one even more after that long night without a fan or air conditioner. I had plans to restock on groceries during that Friday morning but with the city devoid of power that was not going to happen; Caracas was dead and I still had no way to inform myself of anything.

Power came back temporarily sometime around 02:15 p.m. I managed to turn on my TV only to see that the usual game of blame had begun. Maduro’s regime blamed the opposition (and Marco Rubio of all people) for this new “Electric cyber warfare against the power grid’s brain” even though all of Venezuela’s power grid facilities were long since militarized.

The socialist regime rapidly crafted a narrative that exempted them from any responsibility — it’s what they’ve always done, it’s what they’ll always do even when they stop being in power. They’re the heroes to this tale, Bellerophon against the Chimera, and heroes never do no wrong.

I heard a commotion outside our apartment. A neighbor and his daughter were stuck in the elevator as they were heading down to check on our water pump’s status. I joined some of my neighbors and we were able to get them out of the elevator, it was halfway in between floors. The rest of the neighbors tried to calm down the little girl — she was quite scared, but the worst had passed.

Another pitch black night came, and I sat down to talk with my brother about personal plans, the future, and all that stuff. He’s a very introverted man and has it hard when it comes to socializing and speaking his mind, but we had good talk and he was out of that mental shell of his. I didn’t had enough candles because, believe it or not, they were more expensive than an entire month’s power bill at the time, so I was a bit frugal with them, even though I constantly used them to pray, I just hadn’t restocked at the time.

I could hear a few protesters not too far away but couldn’t pinpoint their location nor see them. A chorus of “Maduro, Coño’e tu madre” (son of a bitch) was yelled from nearby apartments as the evening hours began.

The next day, a Saturday I understood what it truly meant to not have physical money with you. Due to Venezuela’s hyperinflation, it was not feasible to go around carrying wheelbarrows of cash like the ones from Weimar Germany. Instead, our local debit cards acted as our Weimar Wheelbarrows.

The thing is, it doesn’t matter how much money you have on a bank when the entire banking network is offline, rendering your cards worthless. For all intents and purposes, the Venezuelan Bolivar was a dead currency during those days.

We walked to our aunt’s place to check out on our family, as they lived in the same building. We played a few card games with our younger cousins in order to pass the time, and we went back to our home as the sun began to set while we waited for an emergency water ration in order to finally shower. Cold as the water was, a shower never felt so good and refreshing as that one.

We then went back to our aunt’s place with a bit of corn flour and our remaining sugar and, together with their coffee and butter, we made arepas for all of us.

One of my older cousins managed to turn on a battery-powered radio and tune in to one of the State’s stations. The usual narrative was being spun: that this was a “terrorist attack from the Ultra-right,” that we shouldn’t protest and instead have faith in “Worker-President Nicolás Maduro.”

Lots of rhetoric and very little information, just like the regime loves to do it. We went back to our place after an hour or so. We hadn’t slept well for the past two days so we tried to rest, a cold breeze kept us chilly — while it lasted.

My inner demons began to run amok; regret, doubt, longing for the old days when I was happier, and so many other things, coupled with my already existing stress of varied nature. I am, after all, a “monument to all my sins,” as the famous quote from a famous video game says, and that night my mind reminded me of it.

I honestly needed someone to talk to that night, but there was no one or no way to do so. I felt like I was going to lose my mind with all the turmoils, regrets, and worries that danced in my head, my only comfort was that my brother was asleep. I eventually succumbed to exhaustion and fell asleep at some point past midnight.

The next day, a Sunday, saw me waking up feeling like crap, and with a headache to boot. The nearby supermarket was somehow able to get fuel for its own power plants, and they were open — better yet, word was it that the banking network was working in some capacity. The place was jam packed, worse than during the days of intense shortages, but I had to go to get stuff to eat and some supplies.

Everyone was trying to get anything they could get their hands on (and afford as well); the checkout lines were near-endless, but after doing countless lines over the past years I became desensitized to them.

That supermarket has a small cafeteria on its upper floor, and you cannot imagine the sheer amount of people waiting in line to be able to charge their phones in one of the few outlets available. The cafeteria’s wifi wasn’t working, and neither was anyone’s mobile data, though.

After almost four hours at the checkout line, the banking network had gone offline again. Although this would become not uncommon as the years went by, the supermarket began accepting foreign currencies, namely the U.S. dollar and the Euro since no one had bolivars to pay with the network down.

I didn’t have a lot of cash dollars, most of it came from the sale of stuff after it was no longer illegal to hold foreign currency, and I didn’t want to spend any of it, but I had no choice, had to pay for what few stuff I had on my cart. I left my brother with our groceries in the line and ran as fast as I could to our home and back.

Power finally came back to Caracas that evening, albeit it remained unstable for a while. VTV, the regime’s main TV channel was airing a marathon of a Turkish drama show, as if nothing had happened. Most of the nation remained without power. Don’t forget that Caracas is both Venezuela’s capital and the seat of power of the socialist revolution, so it is somewhat “spared” from the sheer extent of the collapse of it all — everything outside of the capital district does not have such privileges, though.

Power remained unstable through that next week, and running water didn’t (briefly) return until the end of that week. The power grid never fully recovered from that collapse, and another nationwide blackout took place at the end of March, and then in July.

A supposed failed “military uprising” took place towards the start of May, the circumstances of which were never fully clarified to the public. After that, things just winded down in Venezuela, generally speaking. The protests continued, but each time with less and less strength. People continued to survive as best as they could, and every day the bolivar would become even more worthless.

I eventually was able to get my passport extension, but I still didn’t have a destination out of the country. Most of my time was spent trying to publish content online, working on a broader project, and trying to find a legal way for me and my brother to migrate. My mom’s car started to break down again, and repairing it became extremely uphill, as even spark plugs were hard to get.

Those days saw some rather intense drama moments on my family, and at the same time, I experienced a series of rather unpleasant “offers” that saw to capitalize on my online following for the gain of others, such as invitations to promote cryptocurrency projects that would supposedly “fix Venezuela’s inflation problem,” offers to promote products and services such as importing supplies from Florida to people’s homes in Venezuela, to even offers to write entire books for pennies.

I turned down all of them, it didn’t feel right to sell out like that. From follow-ups I conducted after the fact, it was really the right thing to do.

In addition, the complete normalization of a malady that still exists to this day: Venezuelan pseudo-slave wages, took deeper roots. Public salaries in Venezuela are among the world’s worst, and it’s not like private sector wages are that great either. Whereas someone would earn, say, the equivalent to $5 working at a Venezuelan public office, someone in the private sector would earn $50-100 at best back then.

The absurdly low wages has made it extremely profitable for companies to outsource customer services and other remote work to Venezuela, since you can just pay workers a fraction of the wage. One of my cousins was in search of a job, and there was this supposed “good” place to work as a telephone salesperson. When she arrived, they were only paying $1 per day.

This wasn’t “new” in 2019, it just became more open and ingrained, and it hasn’t improved that much since then. During the 2010s other local industries bloomed because of foreign companies capitalizing on how cheap Venezuelan labor is. Venezuela’s dubbing industry was one such example. Another of my cousins, a local professional voice actor, worked for a dubbing company that did work for international distributors. He, and all others working with him were paid a fraction of what, say, a Mexican voice actor would have to be paid for the same type of work. To this day, he doesn’t get paid much for voice acting gigs.

Believe it or not, the matter of supplies and shortages dramatically improved from 2019 onwards — believe it or not — due to a combination of international sanctions forcing the regime to rescind some of its most draconian socialist measures that asphyxiated local production and the fact that it was no longer illegal to possess foreign currency or trade with it.

The aisles now had a steady supply of toilet paper, flour, rice, sugar, oil, and so much more. The lines became shorter and shorter, until one day, the flow of people in supermarkets became normal, so to speak — but the problem now was that most couldn’t afford them after being crushed down into poverty through so many years of socialism.

The regime, despite hating the United States so much, pretty much lifted all customs fees and tariffs imposed on U.S. imports. This really, really helped improve shortages, but I supposed it also allowed some of its top brass and regime-affiliated people to “launder” money through such business practices.

The lifting of import fees and the improvement in local supplies immediately after some price controls were rescinded helped, yes, but the regime still kept some local regulations that, together with local supply chain problems and corruption, made certain items rather expensive — dairy products, most notably.

Some types of cheese, powdered milk, yogurt, these items were a luxury highly out of reach of many. The disparity between some locally produced cheese versus imported cheese was quite absurd at some point during those years that for me it was noticeably cheaper to purchase “American Swiss Cheese” than Paisa Cheese, an erstwhile household staple in my youth.

And along, came the plague of the Bodegones. Every new week, pretty much, it became common to see locales long-shutdown after its previous owners fled the country or went out of business seemingly spring back to life, most of them selling imported goods from the U.S. such as chocolates, candies, and slop of all kinds and shapes.

Perhaps some were really enticed by these offerings, once strange and impossible to see locally, but it’s not like you can really feed your family entirely with Nutella and chocolates imported from the United States, right? Another thing was the price, the stuff wasn’t exactly affordable, yet some places sold that stuff for rather cheap, as if they were laundering money you’d say. It would be irresponsible of me to assume each and every Bodegon was laundering money, but something was definitely fishy back then.

My young cousin and I visited one such place out of curiosity. We weren’t exactly wearing top of the line clothing, and we didn’t look like big spenders, so there was this one guy keeping a constant vigil on us to make sure that we wouldn’t steal something. In the end I didn’t bought anything because it was just meaningless stuff.

The hunger and poverty among Venezuelans continued to rise, and in one afternoon in 2019 afternoon, I had another firsthand witness of the misery caused by the socialist regime. On that day, I went to my local church to request the inclusion of my mother’s name on the occasion of the 18th her passing.

An unforeseen problem with my mom’s car delayed me until I received help and jumpstarted it. Come think of it, that car must’ve started acting up and delaying me for a reason.

I was approached by a desperate woman and her infant child right as I left the church’s side office, a face I will now never forget. She approached me, full in tears, asking not for money, but for something to eat so she could feed her malnourished child.

No nearby ATM had paper cash, and even if I had been able to successfully withdraw some, it wouldn’t have been enough to buy anything meaningful due to hyperinflation, so what I did was walk to a nearby store and get some things for her. She was grateful, really grateful.

I may be a rash, vulgar person at times, extremely introvert, and utterly inept when it comes to social interactions, riddled with a lack of self-worth and other personal issues that I’m trying my best to get rid of, but one thing is for sure: I’m not an indolent person.

The entire encounter just tore me apart, I hope that things go better for her. Had the problems with my mother’s car not happened, then perhaps I wouldn’t have crossed paths with her — one of those “right place at the right time” occurrences.

I walked back to the car, still parked in front of the church, and took a deep breath, thanking God because despite all the trials and tribulations in my life right now, at least we have a roof and a warm meal every day.

Maduro, and the socialist regime, underwent a “rebranding” of some sorts, casting away the extensive use of red banners and clothing, and the Chávez eyes stencil in favor of more “friendly” pastel colors pulled straight out of a flag design palette. Maduro also adopted a stylized wavy “M” logo and adopted the “together, everything is possible” slogan. This by no means meant they stopped being haggard socialists, it was just part of a broader campaign to rehabilitate the dictator’s tarnished national and international image.

I spent the remainder of 2019 trying to solve problems, and working for a series of articles for Breitbart narrating my experiences in Venezuela — the very first opportunity to put my work at a professional level, for which I’m very thankful for. My dad had some work-related affairs in Caracas, and he traveled in the company of a friend of his family to Caracas in late October. I talked to my brother, and he armed himself with courage to accompany me — what really helped is that I explained to him that our dad is an old man now, and it’s now impossible for him to carry him and take him away back to Punto Fijo.

We picked our dad up and went to a cafeteria, where we had a serious conversation in which I explained the urgency of leaving Venezuela and how we really, really needed to solve the Italian citizenship paperwork. He once again assured me that he’d look on the matter, but pointed out that the last name typo made it “hard” to solve.

Some days after he left he put me in contact with the ad honorem Consul of Italy in Punto Fijo, who espoused the same excuse as to why it was hard to obtain for us. 2019’s Christmas season came in a flash, and I tried to restore that lost Christmas joy. My brother and I put up a Nativity Scene and some old Christmas decorations. Since we effectively skipped 2018’s Christmas, this was, on a functional sense, our first one alone, just the two of us.

My dad’s youngest brother, who had just finished renewing his Italian passport, found out about our Italian citizenship paperwork situation, and he told my dad that he’d take care of helping us assemble all the paperwork. Unfortunately, he passed away around Christmas that year due to liver failure, and the paperwork he had accrued went missing.

If I had failed at getting out in 2018, and now in 2019, surely 2020 would be the charm — but man, oh man, no one in the entire planet was ready for what was to come.