RECORD OF A VENEZUELAN PARIAH

III: THE RISE OF THE FIFTH REPUBLIC

January 1999, I was now 11 years old, and living through the last days of my life in Maracaibo. Hugo Chávez was weeks away from taking office — the final days of a now long-gone Venezuela.

Chávez took office on February 2, 1999. On that day, he swore “before God, the Nation and my people that I will enforce and promote the democratic transformations necessary for the Republic to have a Magna Carta adequate to the new times, based on this moribund Constitution.”

In other words, he reiterated what he had been saying throughout his campaign, that the first and then-most important goal of his Bolivarian Revolution was to change Venezuela’s constitution, to “refund” it into a Bolivarian Republic.

My life went through a major point of change that began days before that February inauguration day, and through circumstances that, without a doubt, were tied to the changes of the country.

At the time, Vargas, a coastal region close to the capital city of Caracas and home of Venezuela’s main airport, the Simón Bolívar International Airport, had finally become the nation’s 23rd state. Today that state goes by another name, La Guaira, after the socialist regime “decolonized” its name.

Through a series of circumstances, none of which I was ever privy of, a former basketball player and “star” in my uncle’s team ended up becoming the new head of Vargas’ legislative assembly, which required to be staffed. In light of his friendship with my basketball-savvy uncle, he extended a job offer to my mom and one of my aunts to relocate to La Guaira and work there. My mom, in light of our financial woes, and her lifelong quest of giving my brother and I a better life than the one she had, took the offer.

The pay seemed good, and it’s not like my mom was in a position to choose, as she didn’t have the means to rent a place on her own at the time, as we were living in a bedroom on my grandmother’s place. So, with hopes set on the horizon, my mom, brother, grandmother and I took a plane towards Caracas.

I left behind friends, toys, the Marist school I loved so much, my friends, and someone who perhaps, could’ve ended up becoming my first love in life — I hoped she lived a good life because she and her family were very kind to me as a kid, and I’ll never forget that.

Before that move, I had only been to Caracas for a couple days here and there, the longest streak being a roughly month-long vacation I had in 1997 when I accompanied my grandmother. Caracas is a much different and larger city than Maracaibo, and I was a strange kid in a strange city. Everything seemed and was different: the weather, actual 24/7 running water (albeit colder), and even cable TV channels that were not available in Maracaibo at the time such as Nickelodeon.

That wasn’t my first time staying at my aunt’s place, but this time it was different, we were all crammed together in a small room, mom, brother, grandmother and I, who slept on a mattress on the floor so they could sleep on beds. My mother had to wake up very early in order to take a bus to La Guairá for her work; while the pay was as good as it was promised it was very taxing for her. I remember there being some delays in the initial payments, so we were running on the fumes of her savings, in addition to my aunts and grandmother pooling resources plus the aid from an uncle here and there.

Here’s the kicker, though, my dad was unaware that we had left Maracaibo, and he only found out because I, in my stupidity, slipped that tiny detail through the phone, much to the justified collective anger of those around me.

I didn’t go to school during those first weeks in Caracas because of the dwindling finances and because things were rather hectic back then. If you’re of Hispanic heritage like me, and from a large Hispanic family, you know how hectic things can be between relatives, cousins… so yeah…

As a sort of “stopgap” workaround, my mother, who always valued education above all else, had me call that friend I mentioned above, she would give me some info as to what homeworks she had been assigned, and what stuff she saw as class. Since I had my textbooks and other stuff from the Marist school, I’d read them on my own based on her info — thing is, that apartment, and living with so many cousins at once, is not a good study environment, so I rapidly became the “nerd” and “brainiac.”

I was eventually enrolled in a school on La Guaira once the salaries started pouring in, which meant I had to wake up very early to take the bus with my mom. I used to like going to school in Maracaibo, but this, and the rather crammed living situation was what perhaps, pushed me into a long-lasting path of me dreading and loathing the idea of going to school, something that took me years to overcome in Punto Fijo — especially when I didn’t know any of those kids, and had no one to talk to, so I felt isolated at school.

I was off the loop in classes, had no friends, and those were the earliest days that I can remember of being the youngest kid in the classroom having a direct impact on the different interests of other kids, some of which were entering puberty. Once again, I felt like an outsider.

These changes occurred right as Chávez kicked in his plan. On April 25, 1999 Venezuela held a referendum to ask whether or not to begin the constitutional proceedings, to which an overwhelming majority voted in favor. Three months later, on July 25, another election was held to choose the members of a National Constituent Assembly (ANC), which, shouldn’t surprise you, was majorly composed of Chavistas.

It was during this time that my brother started to show signs of his mental condition, which naturally immediately worried my mom. My aunt, while I have much to criticize her for, did help my mom financially so that he could receive therapy. I remember accompanying them to some of the sessions, which involved exercises with shapes, toys, and other stuff such as Therapy Putty and things like that.

Just as the country’s politicians debated the changes of the new “Bolivarian” Venezuela that was to come, my life saw some notable improvements. I was still sleeping on a mattress on the floor, yes, but my grandmother convinced my mom to put me out of that school in La Guaira that I hated so much and instead had me enrolled on a small one closer to that apartment, my grandmother said she’d worry about picking me up in school and all that, allowing her to focus on my brother’s therapies and her work.

I also got my very own PlayStation console and a modchip some days later, allowing me access to a multitude of games for cheap, one of which being Final Fantasy VIII, a game that would become my haven from all the bad and the impending divorce drama that would erupt between my parents a few months later.

I didn’t have many friends but bonded with a few peeps due to the Dragon Ball Z hype at the time. Right before they ultimately chose to divorce, my parents had one final vacation, which, as of the time I’m writing this, was my last one so far. It seemed like things were finally getting on track towards improving, or so I thought.

Before I knew it, sixth grade was over. It was time for High School: seventh grade. New uniform colors (We color-code our students here), so gone were the white chemise shirts, now I had to wear the light blue one for the next three years at least.

I was enrolled in Pestalozzi, a school located in El Paraiso in Caracas. Again, a new kid in a new school. My brother was enrolled in pre-school there as well. The first days were okay, took me a while to adapt to the new high school schedule, most of the kids in my

class knew each other for years, so they had their own cliques and inner circles of which I wasn’t part of. My Seventh-Grade experience was as turbulent as the country’s political climate. Once again, I dreaded going to school, I wasn’t sleeping in the best of conditions.

My mother got another job offer, this time in the Perez Carreño hospital, the same one she had studied Pain Management and Palliative Care in a few years past. She would eventually become the head of the hospital’s pioneer Pain and Palliative Care unit, a position she held for sixteen years.

December 1999 came, and virtually everyone in Venezuela was nervous as to what would be the outcome of an upcoming referendum to approve or reject the new Bolivarian Constitution — in addition to the collective turn of the millennium stuff like Y2K and all that.

We all went back to Maracaibo for the holidays, and stayed at our grandmother’s place. It was a bittersweet albeit cathartic moment for me, going back to Maracaibo for a couple weeks, but unable to check on my old friends and school. But hey, I was able to use my old computer again after almost an entire year without it.

December 15, 1999, a date highly infamous in Venezuela, not just because that was the date of the referendum that approved the new constitution, but also because of the Vargas tragedy, a series of flash floods that killed tens of thousands and caused widespread destruction. Chávez, perhaps so as to not have his special day tarnished by nature, infamously quoted Venezuelan Independence Hero Simón Bolivar, who once said,“If nature opposes us, we will fight it and make it obey us.”

He did not, in fact, was able to make nature obey him. Vargas (or La Guaira, if you don’t wanna be a colonizer or whatever), never fully recovered from that tragedy.

There we were, the much anticipated year 2000. No flying cars, no lasers, no spaceships, as people claimed we’d have back when I was very little — but hey, my uncle drove some of us back all the way from Maracaibo to Caracas, which allowed me to bring my old Pentium I computer with me.

The change in year, to me, felt like we had been transported to a completely different era, of innocence lost, of a very cruel tragedy on the same day voters approved a new constitution — talk about bad omens. The mood in Caracas, to me, never felt the same as before December 1999.

Back then, there was this rather innocent approach to the revolution, perhaps because most couldn’t fathom the calamities that were to be unleashed in the years ahead. Political diatribe will always exist between opposing forces, but at least you weren’t at risk of being imprisoned for “hate speech” for dissenting back then. One way I can exemplify the slow but assured erosion of the right to dissent and freedom of speech in Venezuela is that around that time there used to be a theater play called La Reconstituyente, and it starred a group of locally well-known comedians who parodied Hugo Chávez, other politicians, and Chávez’s calls to write a new constitution for Venezuela.

Today? A simple social media post, a video ridiculing the socialist top brass, or having a meme in your phone can be grounds for arrest for committing “hateful” speech.

The political tensions continued to rise more and more, and at some point, the opposition organized the first Cacerolazo I experienced in my life. Long story short, a Cacerolazo is a peaceful form of protest against someone or something that involves banging empty pots, pans, and other utensils. I cannot tell you what was the reason for the protest, because I was 12 years old and utterly clueless — but what I can tell you is that if you give a pan and spoon to a kid alongside a carte blanche to make as much noise as possible, then you can be sure said kid is gonna have the time of their lives.

Be that as it may, though, my school grades were a far cry of what they once were, and coupled with my parents’ divorce, and my early stages of angsty puberty, I had little to no motivation to even try. My mother started earning some sponsorships to travel to other local cities and foreign countries to participate in medical conferences, which did her some much-needed good, because it allowed her to travel, ease her mind from all the troubles at home, the divorce most of all.

A new, much more important election was on the horizon, the so-called “Mega-elections.” A new constitution meant a “reboot” of the republic, and this new fifth republic needed new publicly-elected positions, president, governors, mayors, and members of the recently-created National Assembly, a monocameral entity that replaced the now-extinct bicameral Congress.

A person whose family was a longtime friend of ours, offered my mom and grandmother the opportunity to rent a place on our own, and at last, after so long, I had a room of my own. This change occurred days before the Mega-election. I do remember a blackout occurring on or before that day, a cousin making a joke voicemail message about the event.

Turbulent as these elections were, they served to further cement Hugo Chávez in power. Another political diatribe arose during those days pertaining to Chávez’s presidential term. The new constitution, at the time, established a two-term limit for the President, no more, no less. Chávez technically had already served a term after winning in 1998, but the Supreme Court ruled that because this was a “new” republic, that term did not counted, so he essentially got a freebie 2-year term that didn’t count towards the term limits, with his victory at the 2000 election now representing his “first” term.

With that out of the way, he began consolidating his rule in and out of the country, through actions such as establishing “cooperation” and free oil shipments to Cuba, at the time ruled by his mentor, late communist dictator Fidel Castro — a man that, I may avail myself of the opportunity to point out, was welcomed with “open arms” by a group of some 911 pseudo-intellectualoids (artists, journalists, etc) in 1989.

Seventh grade was a disaster, and eighth grade was much worse. I wrote a three-parter (plus an epilogue, because I can’t count) about those days, should you fancy taking a break from this lengthy entry.

Chávez’s proximity to Castro, and Chávez’s infamous Decree 1011 was the very first opposition he found to his plans. The decree called for the creation of regulatory and supervisory entities in schools — which, suffice to say, no one with two brain cells would be in favor of. The Venezuelan opposition and civil society rightfully renounced Chávez’s “ideologization” plans and he ultimately withdrew it. If anything, this served to test the waters and to know that they had to keep slowly boiling the pot rather than go all in at once, the time was simply not right.

The other boiling pot, though, the one of civil unrest, began boiling throughout the remainder of 2000 and 2001. Around that time, my aunt, with the help of an uncle, helped my mom enroll in a housing program for professionals, and she ended up getting assigned an apartment on the same floor as the one my aunt had just been assigned, albeit significantly smaller.

The apartment only had one bedroom, but since it was located on the ground floor, it allowed for an expansion that ultimately allowed the construction of two other bedrooms: a new master bedroom for my mom, and a comfortable one for my brother, while I kept the original, now smallest bedroom.

We never had enough money to finish all that construction though, as most of it went onto the mortgage itself, which was more important. Finishing that place up, or figuring out a way to sell it, is among the list of pendings things on my head, but one that I can’t solve right now either way. I’d go back to having to sleep on a mattress on the floor between late 2001 to 2003, but that’s beside the point.

That part of Caracas was much peaceful at the time, it had a few commercial locales, bakeries, nearby fast food chains, and other stuff. A nearby mall had a pretty chill cyber cafe that sported some of those famous iMac models from the 1990s. That mall largely, and I mean, largely, depended on the activities of Televen, a local television channel, which had its main headquarters there. Televen eventually moved, and that mall would slowly but surely begin a slow death.

I visited the mall at some point in January 2022, after the collapse of Venezuela and the COVID lockdowns… as dead as it could be, with almost every place closed, the cyber cafe, which shut down many years ago, still has one of the iMacs left as a reminder of what once was.

Those last months of 2001 were another cathartic moment for me, largely in part because I was not going to school during those days, courtesy of a nasty toenail infection on both my big toes, which necessitated two surgeries to properly fix throughout the second half of 2001. I was still bedridden when the September 11, 2001 attacks happened. Even though there was really no chance of it ever happening. I remember people wondering if the twin towers of Parque Central in Caracas would suffer from a similar attack. A fire did happen in one of the towers in 2004, but that’s a whole other unresolved matter.

December 2021 was one of the last real “peaceful” Christmases in Venezuela that I experienced, if not the actual last normal one. Although I was unable to wear shoes at the time due to my surgeries, I was able to go out again, accompanied my uncle and cousins to an auto show, and my mom and I put up a full set of Christmas decorations: Nativity scene, tree, lights. I finally got a new PC during those days, going from a Pentium I 166mhz all the way to a Pentium IV 1.4 ghz, with 256mb of RAM, and an Nvidia Geforce MX440, the upgrade was massive.

I actually started ninth grade some months after its normal start. I wrote a three-parter in 2022 to mark the 20th anniversary of the best high school days of my life, short as they were. For the first time since moving to Caracas, I felt like part of a group at school.

2002 was undoubtedly a very complex and turning point for Venezuela. Before it, Venezuela’s lexicon had already begun to change, but this was the year that I experienced more people openly say that they were with El Proceso “The [Revolutionary] Process” or they where an Escualido (“Scrawny One,” a term coined by Chávez to deride his opponents). Merchandise was sold from both sides on websites such as Terra, that much I remember browsing one day out of curiosity on my then-new ADSL line.

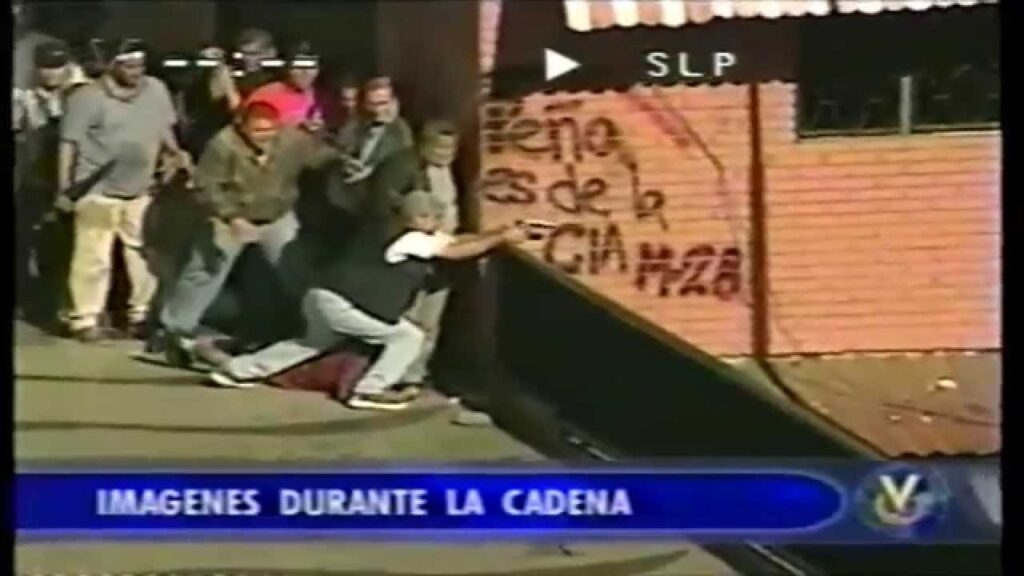

The conflict between the Revolution and the opposition, which had been boiling for about two years, erupted all the way to a series of protests and nationwide strikes in April 2002, which culminated with Chávez’s short-lived ouster on April 11, 2022. Let’s be real, even though it was ruled as a “vacuum of power” it was a coup attempt, a much needed coup attempt, one that needed to succeed for the good of not just Venezuela, but the region and beyond as a whole. It just didn’t succeed, that’s all.

What has never had a shadow of a doubt, though, is that about 19 people died after pro-Chavista forces ambushed and shot at protesters while perched all the way from the Llaguno overpass bridge. The regime insists to this day that those people, of which there’s video footage of them shooting from the bridge, were “defending” themselves from the “aggressive” protesters.

I was at home on that day, April 11, 2002, a date that’s now part of the mythos of the socialist regime. On that day, a massive protest in Caracas against Chávez unsuccessfully attempted to reach the Miraflores presidential palace. Chávez held a mandatory broadcast so as to prevent coverage of the events, the channels defied the orders and broadcasted it side by side with coverage of the protests. In retaliation, the government briefly shutdown all channels.

Those events culminated with one General, Lucas Rincón Romero, stating that Chávez had “accepted” his resignation. That should’ve been the end of the tale, but no, he managed to weasel his way back in through circumstances that perhaps will never be fully disclosed in their entirety.

He returned to power after a brief ouster and, crucifix in hand, called for unity and understanding, all lies.

The protests caused me to lose about a week or so of classes, which I spent playing Halo on my brand new Xbox after my aunt gifted me the elevated sum of half a million Bolivars, which I spent on the console and a copy of Halo.

By the time we all came back, the ninth grade classroom was not the same after those turbulent days. Teachers would spout their political stance more openly, often during class time, students as well.

The most emblematic case was our Castilian and Literature teacher: Mrs. Elsa. She was a fervent defender of the Revolution and all things Chavez, we’d often pit her against Marisela, the most outspoken pro-opposition student in our classroom, who I vividly remember saying that journalist Patricia Poleo was one of her inspirations.

While it was somewhat entertaining to see an adult and a teenager go back and forth on a political debate (mind you, this was long before this was common practice on today’s internet and social media plagued world) our ulterior motive was to burn through as much class time as possible so as to not do anything.

Several protests took place before and after April 2002, as a result, quite a few school days were suspended, tests were rescheduled, and activities were cancelled. Most parents did not want to risk it and send their children to school amid all that uncertainty, my mom being one such parent. The school I went to enacted a policy in which there would be no repercussions in attendance if they chose not to send their kids.

We all sure missed a lot of classes because of this, and as a result, the overall quality of our education did diminish, and in many cases, felt rushed due to the time constraint caused by protests. This is a problem that, due to Venezuela’s cyclical moments of intense protests over the past two decades, has continued to exist through time, and was only stopped and replaced by a worse problem: the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns.

I ultimately passed ninth grade, and it was time to enter the final two years of high school — time to ditch the blue chemise and don a beige one, as Venezuela’s uniform norms call for. The thing is, my mom had this rather bad idea of pulling me from that school and enrolling me in a new, big school that opened near our apartment.

My tenure in that new school was short-lived. The classrooms were great and everything was brand new and flashy indeed, but I couldn’t establish friendships with anyone, I felt

like a complete stranger again. Then, one day, in my eternal naivety, I told a group of people that I had some extra cash in my wallet during P.E. class. Right on that same afternoon, two strangers tried to mug me on my way home because someone “tipped them off that I had money.” It was one of the worst experiences of my life. I ran as fast as I could, they caught me up; I yelled but there was no one nearby. I tried to fight against them until I was able to toss one of them to the street, miraculously, a car happened to pass by and almost ran him over.

That lady saved me, God bless her. I ran towards my home and didn’t want to get out of it for some time. I refused to go to school ever again, and I didn’t, and there was nothing my mom would ever do or say to convince me. For some reason, she caved in, she shouldn’t have.

This incident, which pushed me towards being a teenage recluse immersed in video games and the internet, happened right before a new boiling point in the Venezuelan political crisis. The Venezuelan opposition launched a much longer, much stronger nationwide strike and protests, which the socialist regime has historically referred to as the “Oil Strike.” This over a month-long strike essentially paralyzed the entire nation.

The idea, in simple terms, was to generate enough pressure that could lead towards the permanent ouster of Hugo Chávez, which, you can guess, did not occur.

That Christmas of 2002 was quite bleak, suffice to say. The country was shut down, leading to shortages of a few stuff as most factories were not producing anything. Fuel and cooking gas was hard to come by. Soft drinks, a must-have for most Venezuelans, especially during Christmas, were very hard to come by, to the point that I remember drinking some dubious offbrands allegedly smuggled from Colombia and sold by local resellers.

I didn’t do much during those days other than video games, and bricked my then-modded Xbox through a botched modchip firmware upgrade that I only did out of my incessant curiosity. This incident, for better or worse, pushed me more towards using our computer as a main source of entertainment — a foundational and crucial moment that largely contributed to everything I do these days.

2003 came in, and with it came the end of the failed strikes, and along came the implementation of two major socialist policies whose catastrophic consequences were felt the most about a decade later, you’ll see.

The first, was Hugo Chávez’s decision to implement a draconian currency control exchange system through a brand new office known as CADIVI, a name that will strike fear to those that remember it. As a result of a noticeable drop in foreign reserves, capital flight, and exchange rate shenanigans.

Those iron fist controls — not new to Venezuelans from generations before mine — established yearly caps in the amount of foreign currency Venezuelans had access to for trips abroad, online purchases, foreign education and medical expenses, among others. Similarly. Similarly, controls and requirements for companies were imposed for their imports and other related transitions.

The second, was the implementation of price controls on basic items such as toilet paper, rice, oil, and others. For a time, these two policies seemed to accomplish their intended goals — but like a tiny patch of mold, they festered and rotted the country from the inside out and had a large contributing factor in the collapse of Venezuela during the 2010s, but let’s not skip ahead for now.

One of my cousins and I started dabbling in the world of online PC gaming, first through pirated copies of Quake III Arena, and going all the way to one of the video games I had nothing but the fondest of memories: Star Wars Jedi Knight II: Jedi Outcast.

While I duked it out, gun and lightsaber in hand, with strangers and some people who tho this day I keep in touch with, the Chavista government and the opposition engaged in what would be the first of many, but so many rounds of “dialogue and negotiations,” none of which, I must stress, ever yielded tangible results towards restoring democracy and normalcy to Venezuela.

Those talks were overseen by the Carter Center among other actors. The country’s turmoil appeared to calm down, but there were protests and demonstrations here and there.

One thing that is worth mentioning is that that time period (2001-2003) was an era without smartphones, with most households in Venezuela still rocking 56k connections, and social media wasn’t yet a thing (It was a better, wilder, internet, that much I can say).

Still, both sides of the Venezuelan political conflict had their fair share of online presence. For example, at the top of the Chavista side was Aporrea, a pro-government website with its own message board. Nowadays, that website became so much of a nuisance to the regime that they had it banned from Venezuela once it started to mildly question their actions.

For the opposition’s side, I do remember them being more centered around nascent message boards and online hubs like the long-extinct MSN, although I distinctly remember websites like Antichavez dot com, which served crudely photoshopped images ridiculing Chávez, Fidel Castro, and other regime individuals — think of them as proto-memes, before memes were a mainstream thing. Some of those edits were definitely not safe for work, and I’d rather spare you the details.

2003 was also the year Chávez went onto creating one of his most powerful assets that helped cement his rule and sway the local public opinion towards his favor: The Bolivarian Missions.

Those were a series of social programs, ranging from education, health, military, welfare. He capitalized on the bad aspects that the failed strike’s left in the public discourse and, fueled by a growing oil checkbook at his disposal, created this vast network of social missions that at first you could honestly pass as well-intended and had their own fair share of success. But the main benefit he reaped from those programs was the amount of international praise he accrued, which helped him obfuscate the opposition and push them further towards a villainous “right wing” role (even though they were center-left at best).

The rest of 2003 was a cathartic blur to me. I kept living as a recluse, spending my days and nights playing Jedi Outcast, learning how to make custom content for it, watching television, and learning much from the world outside of Venezuela through my computer screen as I inadvertently continued to sharpen my English proficiency by interacting with others online.

Those years, which I finally had my bedroom for myself, helped the immature 15 year old me live the wildest of adventures in solitude, finally letting loose my imagination which I had to reprieve for so long after moving to Caracas. The anamorphic plays concocted by my immature mind, where the foundational pillars of what would eventually become my passion project: The Vaifen Saga. The Matrix Sequels, that was another high point of my simple life at the time, I have no qualms in admitting.

2004 arrived, and the Venezuelan political turmoil centered around one major topic: The Recall Referendum against Hugo Chávez.

His regime’s very own 1999 constitution introduced provisions to allow publicly elected figures to be subject to a recall vote once they have served half of that term. This would’ve been the most poetic end to his damned presidency, right? But real life is not a movie, and you don’t always get those happy endings.

In order to get to that point, the rules state that the electorate must present enough signatures to the nation’s electoral authorities, and upon verification, the whole process continues all the way to the election.

Chávez had a strong and solid popularity, yes, but the country remained polarized, polarized enough to have people expose themselves to sign the recall requests. The regime did not take any chances, so they took steps to corrupt the process all the way — and retaliate against those who dared sign.

A pro-Chavista politician named Luis Tascon requested, as was the “right” of the ruling Fifth Republic Party, a copy of the registry of everyone who signed. He took that data, had it compiled in a rudimentary software known as “Maisanta,” and distributed via CD-ROMS (keep in mind the internet was much simpler back then and not everyone had access to it).

The “Tascon List,” as it became to be known, is still used to this day to discriminate against those who signed up to recall Hugo Chávez, barring them from obtaining jobs, and are often denied benefits.

While all of that unfolded, though, my family had a more pressing matter at hand: The youngest uncle on my mom’s side, Vicente, was diagnosed with stomach cancer.

Uncle Vicente was more of a father to me than my own dad. He was born with neurofibromatosis (don’t Google that,) and although a series of surgeries in his youth allowed him to have a more normal life, small tumors all over his body always made him a pariah. I never found him odd, because I knew him ever since I was a baby, and thanks to him is why I do not judge people by their appearance, but by their words and deeds.

He used to live in Maracaibo, and during those years I lived there, he’d go pick me up and go to school. He was rather known in that city due to his work at my otter uncles’ basketball team. He never really liked Caracas, but he had moved once he started feeling ill and while doctors diagnosed him.

He passed away in June 2004. We were all devastated by it. His daughter and son were 5 and 2 respectively at the time of his passing. Their mother, not a good person by any measure, didn’t even want them, so they stayed with our grandmother after he died.

My mother was probably the most affected, as she was very close to my uncle since they were the youngest siblings out of that group of six.

The referendum took place on 15 August 2004, spoilers, it failed to pass. The opposition played their cards but were vastly outplayed by the government, Chávez won the referendum and was now bolstered by the victory. To this day, some say that Chavez lost the referendum but his “victory” was agreed upon by both the government and opposition in order to maintain relative peace in the country.

I have no capacity to demonstrate or refute this, and it’s been over twenty years, regardless, if it were true, it wouldn’t be the last time the opposition’s leadership gets branded as a flock of collaborationists, their “deals with the devil” have incurred a heavy toll on the country as a whole.

Chávez went on to establish ALBA as a counter-power to America’s ALCA (Free Trade of the Americas). Cuba’s influence in our country became stronger, while at the same time Chávez began spreading his influence throughout the region, planting the seeds of what would then become a set of allied governments at his disposal over the next years.

2004 was a turning point in the Bolivarian Revolution for sure, but I think this is when I started to notice the growing, essentially irreparable divide among the country. The media was a reflection of this, at the time. RCTV, the oldest TV channel in Venezuela, now long banned and gone, had always opposed Chávez upfront, but now they were dialing it to eleven, same with Globovision, Venezuela’s only television news channel, which ultimately was sold out to regime-affiliated people and became “neutral.”

Another highly important development that served as bedrock for the censorship and mutilated freedom of speech that Venezuela has these days took place towards the end of 2004: The RESORTE law.

That law, whose name translates to, “Law on Social Responsibility on Radio and Television,” is a highly controversial legislation that is essentially a censorship wolf in sheep’s clothing. The law states that it seeks to promote “social responsibility” when it comes to media access, to allow independent creators a space in broadcasting, promote indigenous voices, content safety guidelines to prevent children from accessing innapropiate material, and whatnot.

In truth, the “well intended” articles such as establishing the parental ratings and the hours in which certain types of content can be aired, the barring of “naughty” ads like the hot line ads and erotic movies that used to air at late night, RESORTE kneecapped private media by forcing it to air government propaganda at an hourly basis (which also reduces available air time for private ads, for example), cede some airtime to “independent” creators, and tacitly prohibiting some stuff from being said out of fear of fines.

It was highly condemned as a “gag law,” and with good reason.

Venevision, the other major national television channel, was openly anti-Chavez as well, but during the aftermath of 2002’s failed coup and 2003’s “oil strike”, they took a more neutral approach, they self-censored along the way.

2005, a year where I had to get my shit together, so to speak. This is the part where I admit for the first time that I got a high school diploma through “green roads,” so to speak, due to my refusal to go back to school.

My mom put me in an ultimatum: Either start figuring my shit up and pick something to study (preferably something that’d start in the impending next semester) or get fucked, to make things short.

At first I didn’t feel ready to go to College, I don’t think I ever did, and I actually hadn’t given much thought about what I wanted to study. Medicine was one of the first choices, following the steps of my parents and all, but I had so many self-doubts at the time, so I settled for something that you could say is a lesser version of what is known as Computer Science in America: an “Informatics” course at a nearby private tech institute.

I spent those final months of 2005 adjusting to this new “pseudo-college” life, a far cry from what my online friends had told me about, but it was what I had chosen, to take backsides. I saw myself returning to a classroom after so many years, with a high school diploma I, by no means, had earned, but had under my name.

At first I kept to myself, until I slowly began establishing friendships with some of my fellow students after we found common interests such as anime, movies, and video games.

Those years which I spent as a recluse, especially from 2004 onwards after Ragnarok Online became my main game/haven and I began browsing 4chan upon an RO friend introducing me to it, where the years where I was finally able to embrace that which one calls “weebness,” as in, interests in anime, Japan stuff, and whatnot. I grew up in an environment where this was considered unacceptable and against the cultural norms, which dictated that my interests were “normal” things such as baseball, beer, partying, etc — something my cousins often reminded me of, because I was still liking things like Dragon Ball despite being 15.

While I didn’t have the same social skills as some of my classmates, I did know about Pool’s closed, Desu, Richard C. Mongler, and other memes of the time, yes, even Pedobear. Pool’s Closed, most notably, was a descriptor I shared with my friends at the time to use against our Math teacher, who kinda looked like the meme.

Things were starting to slowly take form for me, and most importantly, my mom was happy that I was finally pursuing a career — until I messed that up too…

The main political event of 2005 in Venezuela, without a doubt, was the 2005 legislative elections, as it was time to choose a new parliamentary body for the next five years. Days before December 4 2005, the day of that election, the Venezuelan opposition suddenly announced that they would withdraw all of their candidates as a form of protest due to the distrust in the electoral authorities and their plans to use fingerprint scanners as an additional layer of Voter ID. The vivid memory of the “Tascón List” and its consequences still fresh in the collective.

As if the regime would care, they basically ran against themselves and other pro-regime parties, effectively securing full control of the parliament for the next five years.

Hugo Chávez ended the year knowing that he’d have a completely loyal parliament once it was sworn in in January 2006, while my family ended the year with another tragedy.

My grandmother, whose health had been deteriorating after my uncle died in 2004, had a stroke in mid-December, moments after she spoke to one of her sons and another through the phone over a business dispute between them.

To this day, I can still close my eyes and remember that night. One of my cousins knocking on our door asking for help, my brother’s panicked face, my mom, who was on her way back home when it happened, hopping on the ambulance and doing CPR.

There was no Christmas joy for any of us that year.