RECORD OF A VENEZUELAN PARIAH

V: THE PROPAGANDA MACHINE

I left Venezuela on October 10, 2009 and even though I didn’t plan for it to be this way, returned on October 10, 2013. My life, for some reason, is full of numerical coincidences like that.

I lived those four exact years in Suriname, a country I only went to as a sort of penance, defeated by a problem of my own making — but in which I ended up becoming a firsthand witness of the revolution’s so-called “Bolivarian Diplomacy of Peace” and how the Caribbean region became an accomplice of the regime in exchange for cheap oil and other promises.

The trip took almost an entire day because of the way flight routes were set up. The plane departed from Caracas in the morning, and arrived at noon at Trinidad & Tobago, where we had to spend the entire day waiting for the plane to Paramaribo.

Suffice to say, I arrived rather exhausted, but received a warm welcome from my aunt and cousins, who awaited me with a now-cold pizza and a Coke. I spent the rest of that midnight chit-chatting and then I crashed on a bed they prepared for me.

At the time, my aunt was renting a rather nice looking small house that I later found out belonged to the mistress of a drug lord who had moved to The Netherlands, which explained the bulletproof glasses, security cameras, and reinforced doors.

Culturally speaking, Suriname is a country much, much different than Venezuela, Colombia, Ecuador, and other countries in the region. Due to its history as a former Dutch colony, they naturally speak Dutch and Sranan Tongo, their creole dialect. That said, English is spoken by almost everyone there, so I had a way to communicate with others — besides, that was the whole reason I was there in the first place.

Now, time for some exposition, bear with me here.

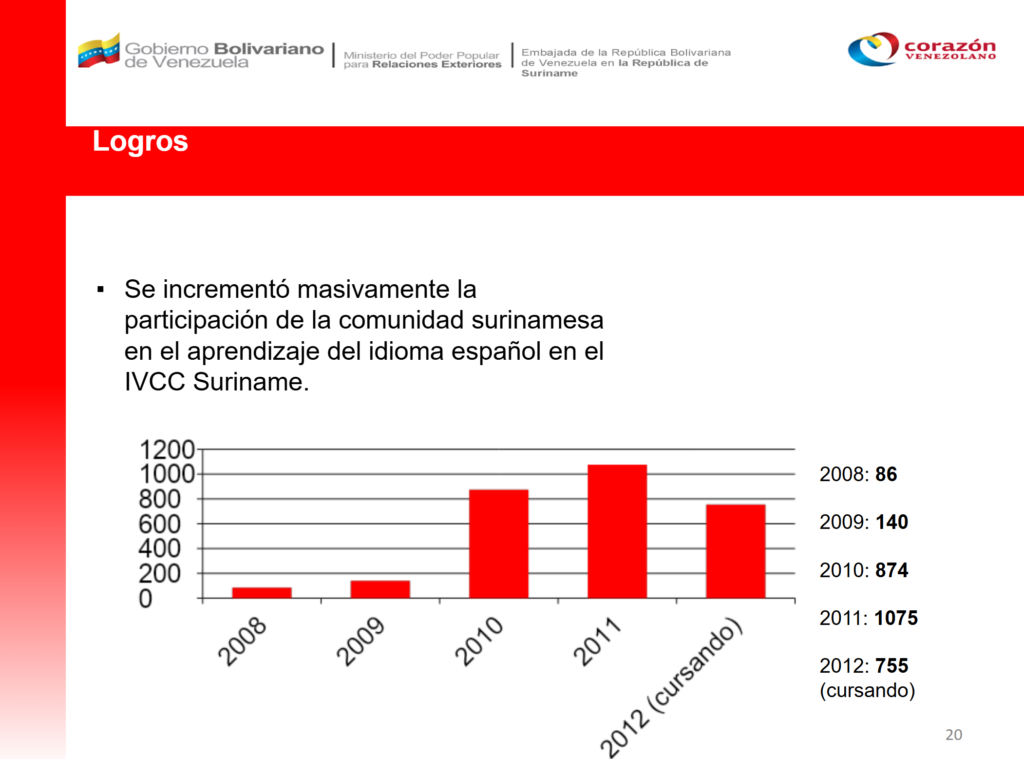

Venezuela, decades before the arrival of Hugo Chávez and his socialist revolution, established Cultural and Cooperation Centers (IVCC) across English-speaking Caribbean nations (if memory serves me well, there should be one in every Caribbean nation or in almost all of them at least). Suriname had one such IVCC. To my understanding, the embassy was relocated there at some point in the late 2010s

The main goal of the IVCC was to serve as a cultural bridge between the English-speaking Caribbean and the Spanish-speaking nations of Latin America. One of their main flagship programs, at least back then, was free Spanish courses that the local community could participate in, which in theory, allowed them to communicate with the rest of Latin America — this noble goal, though, was twisted by the socialist regime, and the centers would go onto becoming mediums to spread socialist ideology, but we’ll get to that in a bit.

Another, rather nice and harmless use of an IVCC that I witnessed was a Santa (or Sinterklaas in this case) event on Christmas 2009 that saw a sizable group of poor kids get gifts, or a multicultural bazaar event in 2011 in which several countries set up their booths. That’s the first and only time I’ve had Canadian beer.

I cannot ascertain if this was the case in every nation with an IVCC, but when it comes to Suriname, the original agreement that both countries signed saw Suriname cede a small lot in the capital, Paramaribo, where Venezuela built the IVCC, effectively turning it into Venezuelan territory almost like how an embassy is treated as such.

In exchange for the land, Venezuela agreed to let the local government, organizations, and others, use their facilities for free; be it for sports, cultural events, or political stuff, with its corresponding approval, of course. Some examples include art expositions, basketball tournaments, dance, etc.

Emphasis on the free part.

One of my aunts, a lawyer working at the Foreign Ministry since 2004, was temporarily assigned to serve in the Foreign Service as Councillor for a brief period of time. She ended up as the embassy’s Charge d’ Affairs ad interim for about four years after several corruption scandals erupted at once involving the former ambassador, who had been there for almost a decade.

Remember the “use the facilities for free” part? Well, it turns out he and other diplomats at the embassy had been charging for the use of the IVCC, and no one knew where that money was ending up at — but receipts were found of people paying the embassy for the use of the facilities, and it wasn’t spare change either.

There were other scandals of a similar nature involving that man, all of which, I was told, blew up at once in early 2009: Dubious bank transfers to Zurich, fund embezzlements, and other illicit activities, including illegal espionage on IVCC staff through hidden cameras.

My presumption is that he was able to do all of that because first and foremost, most Latin Americans do not even know Suriname is a country in the region, and it’s such a small, forgettable embassy that flew under the radar. No one from the regime batted an eye, I guess, seeing as they were other fish to fry. At most there were about 25-30 Venezuelans legally living in that country back then, and the embassy + IVCC had about as many staff members.

That ambassador was quietly removed, there was no major news coverage of it. I was told that supposedly, his removal took place hours after a regional heads of state meeting in early 2009, and that there is footage of former Surinamese President Ronald Venetiaan reaching out to Hugo Chávez in that event to call for the guys’ removal once his office found out.

Be that as it may, my aunt, who was slated to return sometime during late 2009, got a call in April 2009 telling her to take administrative charge of the diplomatic mission while they send an audit team to clean up the disaster. So, for better or worse, what was supposed to be a defined work for a defined period of time suddenly became a lot more.

There are two types of personnel on an embassy: Diplomatic Personnel, as in, ambassadors, Minister Councellors, and other lower ranks, who are the ones with diplomatic immunity and all the fancy bells and whistles like diplomatic, or service passports for the lower ranks.

And there’s also local personnel, regular people who reside in the host country and work as an office clerk, messenger, cleaning staff, and the rest of the normal jobs that you’d find in an office. These abide by local labor laws and all that entails. Always keep in mind that distinction.

A few local personnel heads rolled as a result of the 2009 scandal, and my aunt had to fire some others, such as the former ambassador’s secretary, IVCC director, head of general services, to name a few. Many of them filed lawsuits against the embassy for unlawful termination, but none of them were able to win once evidence of all that stuff was presented. The embassy was left effectively understaffed by both diplomatic and local personnel.

I started that English course with my cousin a few days after arriving. It wasn’t exactly top of the line education, but I was living under a self-imposed penance, so I had no grounds to complain. My cousin had the brilliant idea of getting infatuated with a local Venezuelan that worked at the IVCC, and who was studying at that English academy too — and this is where both stories mix.

Being a small embassy, and in a small country to boot, a small Consular Section office with two computers, a desk, a filing cabinet, and a window booth handled all of the functions that larger embassies would need a full blown Consulate or two to fulfil. Prior to the corruption scandal blowing up, the former ambassador had appointed my aunt at the head of it as the previous diplomat went onto doing other stuff.

At some point, the ambassador wanted my aunt to sign off a tourist visa to a shady Chinese guy who was offering $10,000 for it. Her refusal, and his response, is what led to her and other people digging into the broader corruption probe. Either way, after she was put in administrative charge of the embassy, the diplomatic post of that office was left empty but defaulting to her as the mission’s only remaining personnel with diplomatic status.

A local man who worked as secretary of the consular section for 18 years, was coerced into resigning to help “boycott” the embassy by the group of people that were fired. He presented his resignation on September 10, 2009, the same day my mom gave me that ultimatum to get my shit in order — I am not making this up.

My mom, brother, and other cousin traveled to Suriname to visit us those days. Later I found out that my mom planned to bring me back but didn’t end up saying that part to me, maybe she should’ve and I would’ve returned, I don’t know…

One of the remaining local staff had to cover consular office duties like issuing a visa whenever there was something to do, but this could only go for so long. My cousin had another brilliant idea, and vouched for the woman he had his pants hot for to get transferred there, debuting on the last working day before New Years, of all days.

It is not uncommon for local governments to request “courtesy” visas to government personnel, or “diplomatic” visas if that’s the case when traveling for official government business. On that day, there was an urgent request to issue a courtesy visa to a Foreign Ministry staff member who wanted to visit Venezuela for personal reasons.

That woman, don’t ask me how, but she somehow broke the old computer that had the proprietary visa software installed, and the local tech guy that they had called (embassy’s tech guy was fired too) couldn’t figure it out. My aunt, because she had no one else to call, had me brought to the embassy as a last ditch hail Mary to see if I could help defuse the impending embarrassment with the local government, so I went there. Puzzle solving has always been something I’ve liked to do, computer-related ones even more so.

I didn’t have any tools at my disposal like external drives, USB sticks, or a bootable live Linux distro with me, and time was running out. Most computers were still running Windows XP, including that one, although someone found a copy of XP’s installation disc in the embassy’s storage, no one knew where the CD with the proprietary visa software was at.

What I ended up doing was taking a hard drive from an unused computer, slapped a fresh install of Windows on it, then plugged the original drive as a secondary and try to cannibalize the files from the visa software and, most importantly, find where it’s “savefile” was at.

I moved the folder, everything seemed to be there, including some database files that had the registered visas, previous applicants, and all that. The thing is, the software wouldn’t run because it required Windows 9X .OCX files, which XP didn’t have. As a last ditch effort, I replaced the whole fresh System32 folder with the one from the original non-working installation — it worked.

Because the other staff member was busy, and the software didn’t exactly require extensive training to use, I ended up registering and printing the courtesy visa and then they had it stamped. In any case, I saved the day. Funny enough, the disc with “CONSULNET” was eventually found sometime later and only while someone was searching for something else.

Because of that, my aunt disregarded all nepotism-derived quandaries and offered me the consular secretary position that same night during dinner. The wage wasn’t exactly high, roughly $648 at the time plus roughly $30 as a transportation bonus but hey, I never had that much money in my life at once before, so I took it. It was miles more than my best month doing side gigs back in the day.

My mom was rather displeased because it meant that I had to drop out of that English academy, she eventually accepted it, and we spent a rather interesting New Years. Suffice to say, the woman that broke the computer got fired.

I formally started in that position on January 3, 2010 as a temporary trial position while the necessary paperwork was prepared and shipped back to Caracas, who had the final say. Because of the sudden and urgent nature, and because I was on a student visa, the embassy threw me a bone and filed a formal change of status request on my behalf so I could get a proper work permit.

Technically speaking, I was working illegally during January and some of February, but since I hadn’t been paid yet, nor was I formally under a contract, I technically wasn’t at the same time, because the legal term was that I was “helping.” Eventually I’d get paid via checks since my work permit hadn’t been processed, which I needed to open a local bank account.

When the former ambassador put my aunt as the diplomat in charge of the consular section, he gave her a “bible” of how to handle a consular section. It was a rather well organized heavy binder that detailed the procedures, how to use the visa software, how to generate the monthly reports, and other operational tidbits. I learned all that on the fly. Other than the proprietary consular software, the rest of my work involved the use of Microsoft Word, Excel, and all the basic stuff you’d ever use in an office, seeing as it was an office job.

My mom was set to return to Venezuela shortly after my 22nd birthday. By chance, she was offered a job in one of Suriname’s hospitals. Anesthesiologists like her have come quite rare in the region, and she was a one-of-a-kind doctor.

The job offer came with an amazingly good salary in USD, it was a dream come true for her — however, she declined, as my uncle’s health had worsened back in Maracaibo, and that was more important to her. To make matters worse, my other uncle resumed the family feud, and my sick uncle seemed to be on the losing side, especially after he got kicked out and left with no money or anything, and now unable to walk.

At the time it didn’ t seem like it, but she made the right call, even if neither of my uncles did, and you’ll find out later why.

I started my job at a slow pace and learned things on the fly, getting familiarized with the office environment. I first started with the basics, processing visa applications that had been approved, printing them, putting them on the passports, and all the paperwork that generates. I’d also “assert my dominance” by running that office’s air conditioner at low-ish settings here and there.

It wasn’t exactly the most high-octane job ever, but I was doing something, and I felt helpful. My first “major” consul case was that of an elderly Surinamese man who requested the embassy’s help in trying to find his estranged brother living in Venezuela. He told me he hadn’t spoken to him since the 80s, and all he had was some basic information such as his name, a photo, and where he last lived. Sadly, although I sent the corresponding request back to Venezuela, no response was received from the Venezuelan authorities.

I will say this, having to talk with people who came to apply for a visa or other requests through a booth helped me with my lack of social skills immensely. At first I stumbled and shuttered a lot, but I got the hang of it as time went on.

Since there was not much work to do during those days I “optimized” some things, cleaned up some archives, made a cleaner printable version of the visa requirements, transferred the consular software installation to the office’s “better” Windows 7 computer now that I had the disc to make a jury-rigged portable installation.

On the downside, I started to neglect my weight like never before, and I became far more obese than what I am these days, too much junk food, soft drinks, and sedentarism. That was the worst era of my life when it came to being fat, let’s put it that way.

I eventually started to help with other embassy functions such as English-Spanish translations, drafting non consular internal and external communications, and other office-level work since the embassy was severely understaffed.

To make matters worse, from 2010 onwards, the Venezuelan Foreign Ministry slashed the embassy’s budget by 67% due to a combination of the 2009 austerity decree and the massive corruption scandal. Throughout those years under the administration of my aunt, the embassy was only given the bare minimum operational funds to cover its basic expenses such as the office space’s lease, utilities, and whatnot.

Additionally, there was no more extra funds to hire new staff, other than the allotment reserved for a new ambassador’s secretary position (with a salary of roughly $1,800 per month since that’s what the previous one earned). No raise, no extra bonuses, that was about it, as a result, my aunt often paid extra work to people out of her own pocket.

The saving grace, though, was that the ambassador royally messed up and paid wages in U.S. dollars instead of the local currency as Venezuela demanded, leading to a pending legal matter between the embassy and Suriname’s Labor Ministry.

Most Spanish-English translations were handled by me while those involving Dutch involved someone else. The embassy did have someone working as a translator during those days, but he was caught watching smut on the computer. That small office space was repurposed as a file storage and the location of a file server that hadn’t been set up yet.

The fact that I was busy as a jack of all trades in that office kept some of the negative thoughts in my mind at bay. I had to attend to my job’s own duties as well as the translations, assist in the administration, assume the unofficial role of the charge d’ affairs assistant, and lend an extra pair of hands whenever needed. Several roles for one of the lowest wages in the embassy, talk about a bargain.

I wouldn’t say that the corruption scandal strained the relationships between the socialist regime and the Surinamese at the time, as they were already lukewarm. Despite that, though, Suriname did avail itself of some of the regime’s oil checkbook, as in, they ordered a few appetizers rather than going all in with the full course meal.

One of these “appetizers” of Venezuelan money was $2 million for the construction of two fish smokery facilities in the country. The proposal was presented at some point in 2009, and the Venezuelan regime straight up gave them the money without thinking twice, eliciting surprise from the local authorities who were expecting a degree of friction at least, or so I was told.

Another goal of them was to insert Suriname in ALBA Alimentos, a food division of ALBA, a far-left trade block founded by Hugo Chávez and Fidel Castro in 2004 and which still exists to this day.

Since Ronald Venetiaan’s administration was rather reluctant to go all in on the Venezuelan oil checkbook, the actual, really meaty stuff involving the socialist regime wouldn’t occur until the election of Desi Bouterse in July 2010 and onwards.

For those that don’t know, Bouterse was a former murderous dictator of Suriname and a convicted drug trafficker that was then elected president, so he had all that in common with those that have ruled Venezuela since 1999 — but his 1980 coup succeeded whereas Chávez failed in 1992.

With a new leftist leader in the region willing to have a seat in the Venezuelan socialists’ international table, Venezuela ramped up their relations with the close neighbor, sending advance foray parties to begin talks into what was to come. Since Bouterse had a close advisor that spoke Spanish fluently, there was no need for me to be in the way.

Chávez was originally slated to attend Bouterse’s inauguration in August, but cancelled days before. If memory serves me well, the tensions between Venezuela and Colombia at the time had much to do with it.

Instead, and since they had already prepared an official delegation, Nicolás Maduro represented the regime. The regime spared no expenses, and because the embassy had no budget, they sent a financial “care package” so that the embassy could rent rooms for the large delegation in the country’s best hotel, rent vehicles, hire chefs, and all other expenses.

I served as a translator for some of the Venezuelan officials that arrived. The military requested new computers in their hotel rooms, with state media requesting high speed fiber internet with unrestricted ports and whatnot — you should’ve seen the local ISP’s guy’s face as I translated the requirements, because their ADSL-based service was in no way capable of providing that.

Since I wasn’t the most social person, and I stuck like a sore thumb due to my size, I relegated to doing what I did best: office work, as there was a lot to do such as present delegation lists, request overflight permissions, and so much more. Curiously, the Venezuelan delegation’s protocol staff list included a peculiar name, one exactly the same as this one girl I knew from eighth grade, but I never got a chance to confirm if it was the same person.

One of the most annoying parts was to serve as a translator for Venezuela’s flagship state media channel, VTV during a B-roll footage tour that saw them record the outside of the local church, synagogue, mosque, and other religious temples — not because of the locations, but because they were utterly annoying and lacked basic decorum.

Despite not wanting to be there, I had no choice but to attend the ceremony, sitting a few rows away from the ambassadors, heads of state, and other representatives. During a parade, I crossed paths with Chávez and Maduro’s longtime translator, who asked me and someone else if there was anything fun to do in this country, seeing as at the time there were no cinemas or amenities whatsoever.

The caravan towards the facility was suddenly stopped because Maduro forgot his glasses, and the return caravan to the hotel was rushed because Maduro needed to take a fat dump. I am dead serious. During that time at the hotel, I overheard Maduro complain to one of his closest aids, with expletives, how “some shit” had stung his face.

With all that hecticness out of the way, things calmed down in the embassy for a bit. My work permit finally arrived, and I normalized my situation, opened a bank account, got my credit card, and I was for the first time ever, able to purchase stuff online, what an experience.

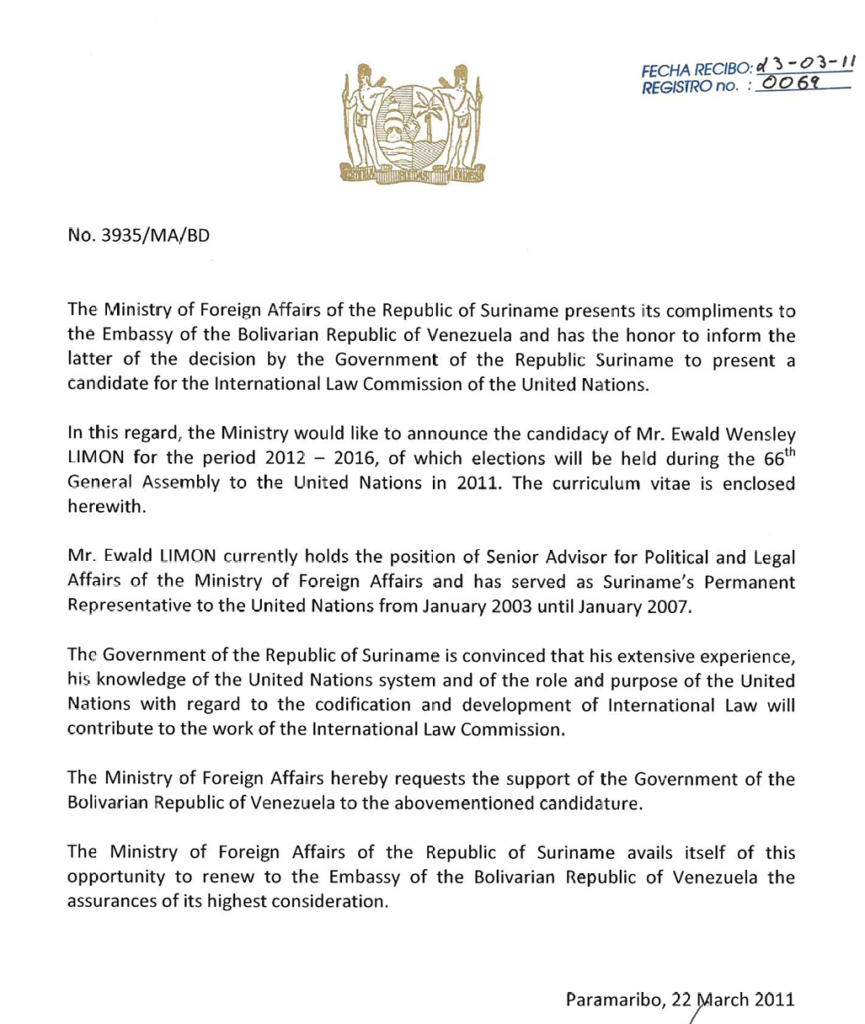

This was around the time when I began experiencing just how easily votes at international organizations are traded like bargaining chips. You see, you may be familiarized with the United Nations passing a resolution calling for a country to stop doing something, or for another country to do something else. These are rather superficial, often symbolic acts.

Beneath all that, though, there are multitudes of job positions in international organizations, who have the ability to influence or request stuff. Let’s say Venezuela wants to have one of its own as head of some environmental

At the U.N. but Suriname wants one of their own to lead the delegation on, I don’t know, sustainable food or whatever. A vote for a vote, you know what I’m saying?

At the same time, if you as a country depend on Venezuela’s oil, are you really going to say no to voting for their candidate in something more important like, I don’t know, the Human Rights Council?

You see where I’m going with this? The vote trading that goes into these international organizations is a power-play hidden in plain sight. This kept getting worse and worse as the years went on. The same could be said for resolutions condemning Venezuela, Caribbean and other nations, bought by cheap oil and whatnot, became a shield for the socialist regime.

Unfortunately for Suriname, despite how much Bouterse and his people wanted to suck on the socialist regime’s “generous” oil tit, they arrived a bit late to the party.

2010 was the year where the shortages of toilet paper and other items became more widespread, and reached international ears more and more. The inevitable collapse of socialism in Venezuela had begun. The regime denied the shortages and instead began blaming supermarket chains for allegedly “hoarding” food. People who wouldn’t fall in line were arrested and criminal charges — case in point, one of my uncles on my dad’s side of the family.

Power blackouts, already a recurring problem, became worse and worse, especially in Zulia. The lack of investment in our country’s electrical grid, and the hundreds of millions that were supposed to go into fixing it that straight up got stolen, began to show its consequences.

Ironic, because my aunt told me that a government official that traveled to Suriname during those days gloated how the socialist regime helped Daniel Ortega by rebuilding Nicaragua’s power grid in exchange for unspecified favors.

The growing hunger led to growing crime, and in one case, it affected my uncle in Maracaibo, whose wife had her car stolen — only for the criminals to return it and apologize out of respect for who he was, I kid you not.

He was widely known for his tenureship at the local basketball team, but at that time, he was wheelchair-bound and penniless after his brother kicked him out of the business over a decades-long feud, he still had a revolver, though. Since she was no longer burdened by my uselessness, my mom had some extra money at her disposal that she used to help her brother in that time of need.

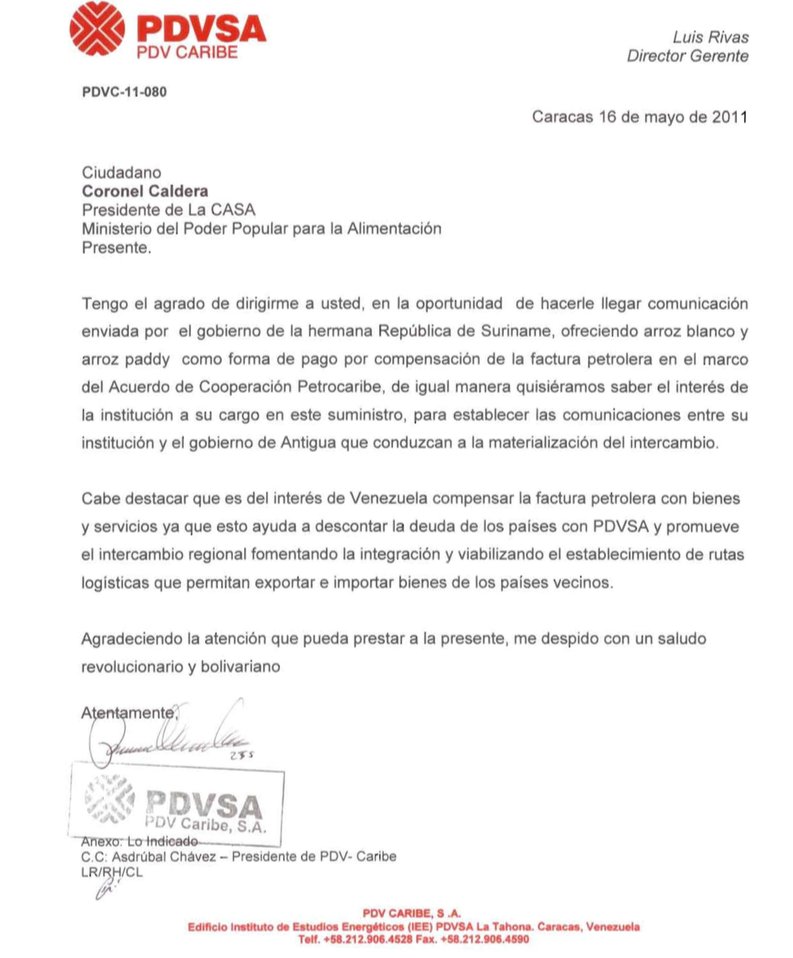

Still, failing Venezuela aside, Bouterse wanted cheap oil like his fellow Caribbean heads of state were getting, he also wanted Venezuelan urea to use as fertilizer, and Venezuelan money for other projects. In contrast, he had rice, something Venezuela was once able to produce enough to cover its own demand and even export before the socialists started seizing everything.

One Bouterse’s closest buddies, who I was told serve prison time in the U.S. on drug charges after being hilariously arrested in a McDonald’s after he finished his burger, wanted to peddle a rather shady wood business. A local businessman wanted a starring role in the potential rice deal, and another one wanted to see how he could benefit by peddling a direct Caracas – Paramaribo flight route. Everyone wanted socialist money, even if it meant becoming accomplices in its atrocities.

The opposition saw an opportunity to recover some ground through the October 2010 legislative elections after abandoning it to the regime in 2005. Although they recovered some seats, it wasn’t enough to cause any dent in the regime’s growing authoritarian plans.

Then, in November 2010, Bouterse finally got what he wanted: An official visit from Hugo Chávez, the “Supreme Commander of the Revolution.”

The opposition saw an opportunity to recover some ground through the October 2010 legislative elections after abandoning it to the regime in 2005. Although they recovered some seats, it wasn’t enough to cause any dent in the regime’s growing authoritarian plans.

Then, in November 2010, Bouterse finally got what he wanted: An official visit from Hugo Chávez, the “Supreme Commander of the Revolution.”

The whirlwind visit took place at a time when flash floods killed dozens in Venezuela and left hundreds homeless. Like back in August, the understaffed and underfunded embassy rushed to get everything ready. This time around, I did most of that work while in the embassy.

Because it was sudden, though, no “financial care package” was sent, so the embassy had to cover almost all of the costs, dragging and diminishing the operations for years.

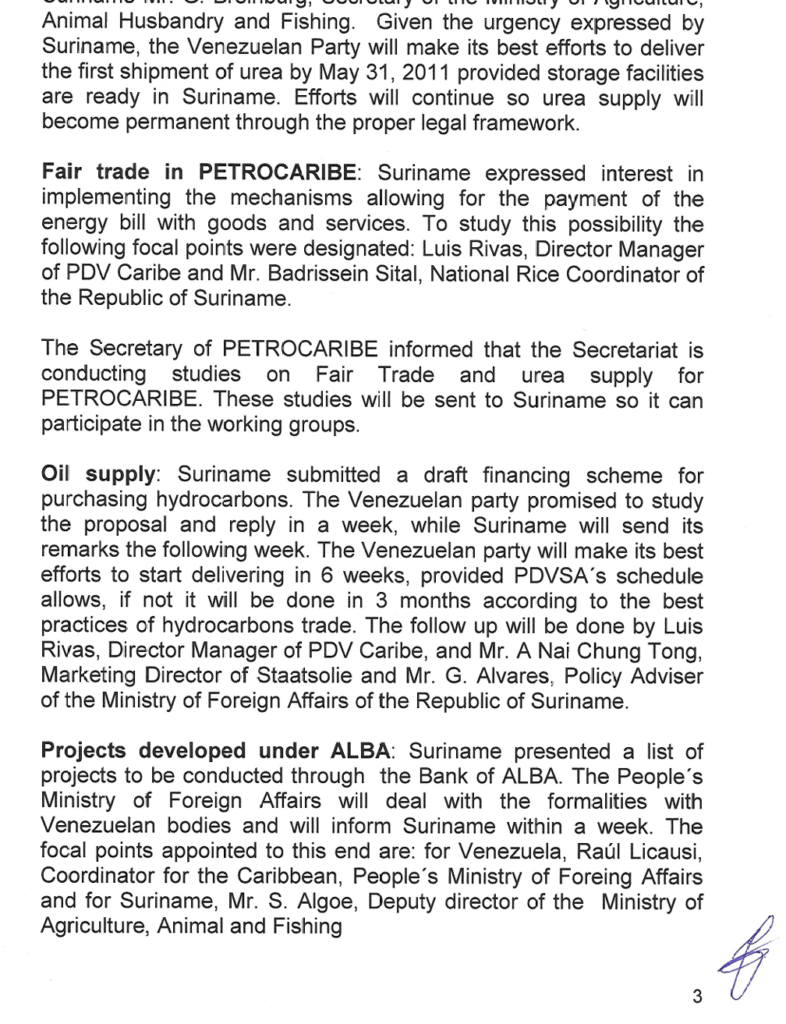

The two “revolutionaries” met, and signed four main agreements: Oil supply, urea, rice, and housing. Gotcha, another country under his belt. “The idea is to make them depend on us,” Maduro allegedly ordered back when he was Foreign Minister.

There was one tiny problem, the four agreements Chávez and Bouterse signed? They were riddled with errors and incongruencies because they were hastily put together. The ones in Spanish had some numbers that differed with the Dutch copy, which were rather beneficial to Suriname.

This had to be discretely solved by the two countries, but it would take some time. As for the original Spanish agreements, my aunt was instructed to hide them away somewhere. I think she threw them in a box or something.

It was during these days that I started to give a more tangible form to that story that I’ve wanted to write ever since I was a teenager. I took the very first solid notes, but I simply didn’t have enough time, not when I was doing the equivalent to five different positions for the salary of one.

At the advice of someone I met over there, in what is a story worthy of its own tale, I reestablished contact with my father. He was non-conflictive for once, I even talked to my half-sister for the first time.

I brought up the subject of our Italian passport, but he responded with his usual repertoire of excuses, saying that it couldn’t be done because of a discrepancy in our last name — a lie I ended up figuring out over a decade later.

My mother and brother visited us again in 2010, this time I had some money to buy them nice gifts for the first time in my life. Once again, she was offered a job in Suriname, but she declined because she didn’t want to leave our sick uncle alone. I really wanted her to take the job so that we’d be together, but alas, it was her call.

Remember the IVCC’s free Spanish courses? Throughout 2010 a new order was issued to “revamp” the courses with pro-Chávez ideological content spliced in between the normal Spanish content. At the same time, it was instructed to boost participation.

For years, the embassy funded a weekend Spanish/Dutch radio show that talked about Venezuela, teaching listeners about its culture, locations, flora, fauna, food, the country, basically. The new order was to retool the show to spread pro-regime propaganda and the “achievements of the Bolivarian Revolution.”

2011 started with me getting hit by pneumonia, I never had proper rest since I had so much stuff to do at work. Venezuela’s situation got slightly worse with each passing day and the opposition was very inert as a whole.

I was now accustomed to neglecting myself in favor of work and everything else, something I deeply regret today. The countries continued to work their arrangements while Suriname began the process to adhere itself to the leftist ALBA trade block. The socialist regime was focused on clamping down on the “hoarders” that allegedly were harming the people (food shortages), and everything just slowly but surely continued to decline.

Their international focus was CELAC, a broad Latin American and Caribbean bloc that was to launch in mid-2011. Most of my non-consular work was focused on translating boring CELAC-related letters back and forth, and serving as translator for delegations in meetings such as the United Nation’s FAO food organization.

As for my my consular secretary job, the only one that I was actually earning a salary for, I had my run-of-the-mill visa applicants, but I also had some crazy cases, such as a voluptuous Dominican woman that desperately wanted a visa despite having no money (red flags of drug mule), a crazy guy that had plans for a “nuclear bomb” that he urgently wanted Chávez to have (they were photocopies of a WW2 history book), and a Venezuelan fisherman so annoying that his captain abandoned him, which is a violation of international law.

There were other, rather tragic cases of human trafficking, that served as another warning that things were rapidly going south in Venezuela.

At some point during the year, two women identifying themselves as Venezuelan nationals were detained by the police. They claimed that they had escaped from a place in which they had been forced into prostitution. The two women told the police and the embassy that someone had recruited them in Venezuela offering them legal jobs, but upon traveling they had their passports and documents seized. According to their testimony, they managed to escape through a bathroom window when no one was looking.

Since they were illegally in the country, they had to be deported, but since they had no documents other than photocopies of their Venezuelan identity cards, we had to wait for Caracas’s confirmation. This occurred at a time when IVCC’s Spanish course was on break, so my aunt, in a genuine moment of humanity, brokered a deal with the police so the women wouldn’t have to be in jail all the way till their deportation.

She had the police send her to the IVCC, and she, out of her own pocket, got them inflatable mattresses and other supplies. Caracas gave the go-ahead. The problem was that the embassy was so underfunded that it didn’t even have emergency passports.

My aunt grabbed a piece of stationary and pulled out some legalese to concoct an “emergency travel document” for the two women, which I then transcribed, had signed, stamped. I put their respective photos and fingerprints, and off they went.

Before one of them left, she told me that although they had no money she managed to snatch what appeared to be a small gold pebble, which she told me she could perhaps exchange for dollars — unfortunately, the “official” exchange rate in Venezuela was so absurdly low when compared to the black market, so I kinda let her know that. Hopefully she listened to me, I hope.

Other similar cases of Venezuelan women forced into prostitution, rescued, and then deported took place during 2011 and 2012. Like the first two, all of them were women from poor rural towns in Venezuela searching for ways to feed their families. Over time, cases like these became widespread in countries like Trinidad, Chile, to all the way to the United States even.

There was another case, around May 2011, that straight up was one of those “small world” moments for me.

At the time, a group of sailors had their boat engine die overseas, and were adrift. Their shanty boat eventually began to sink but thankfully were rescued by the Surinamese coast guard, who thought they were illegal fishermen.

Like with the case of the two trafficked women, my aunt arranged for their stay at the IVCC while deportation proceedings occurred and their identities were verified, seeing as they lost everything when the boat sank.

Turns out, they all came from Punto Fijo, where my father lives at. It also turns out that one of the guys was also named Christian like me, and her grandmother had passed away recently. Guess who did the autopsy? My dad.

At the time, it would’ve seemed like Hugo Chávez’s Bolivarian Revolution were undefeatable, his grip on Venezuela was as firm as ever despite the start of the collapse of it all. His international image was at an all time high, and he had most of the region under his pockets through Petrocaribe and other oil checkbook-funded programs. 2011 was also the bicentennial of Venezuela’s independence from Spain, and boy, the money they burned in propaganda was absurd.

That is, until he announced all the way from Cuba that he had some undisclosed form of cancer.

The revelation shook the entire world, although I’m pretty sure his inner circle knew way in advance. Days before the official reveal, I accompanied my aunt to translate a boring oil deal meeting at Suriname’s state oil company. Funny enough, the embassy driver that was supposed to take us there had a problem with his phone, and I told him I’d take a look at it once I had the time.

He was nowhere to be found, and we ended up going to the oil company thanks to someone who took us on his van. After all that, we were kinda hungry, and my aunt had me go buy some Chinese rice, but right as I was about to deliver it she got a closed door call. Her demeanor was completely different afterwards.

She admitted to me after the official announcement that the call was to let her know what was going to happen, and to get ready to cancel an upcoming CELAC meeting and all related proceedings.

Chávez became less conflictive from that point onward. The man, who had brazenly said he did not believe in God, was now pleading to Jesus Christ for his life in public events; he was always a charismatic man and his condition made him more human in the eyes of the public.

The “Fatherland, Socialism, or Death” mantra, which appeared in almost every regime propaganda and internal memo, was replaced with “Independence and Socialist Fatherland, we will live and we will triumph.”

Unfortunately for Suriname, Chávez’s health was the priority for the socialist regime, and everything slowed down to a crawl, much to the anger of people such as the rice magnate that wanted to peddle his product through the rice agreement signed between both countries.

Most of the IVCC’s events and propaganda shifted more towards Chávez given his health, people wanted to express their support to the “Supreme Commander of the Revolution,” to the point that Bouterse himself asked for the embassy’s help in trying to draft a letter of support.

My mom and brother were slated to visit us for a bit in December 2011, and then visit Italy to attend a medical conference that my mom was slated to participate in some weeks later. Unfortunately, my brother passed out during one November school day.

An MRI revealed that he had a brain condition called Arnold Chiari, and he required surgery as soon as possible or he could potentially suddenly die at any time in the future. The news devastated my mom, who told me to get an MRI myself, which supposedly came clear.

She cancelled her plans, and it was a rather insipid Christmas and New Years. I actually found a copy of her Italy plane ticket when searching for something else, it was a country she really wanted to visit at some point. In what was perhaps a highly stupid move of me, I told my dad what was happening, and he overreacted to both me and my mom, who got mad at me.

My brother’s surgery took place in January 2012 at a time when Suriuname finally got the first Venezuelan oil shipment that they had been coveting for so long. Although the surgery went well, he had a relapse during recovery. It was not a good time for my mom, as the medical debts kept ballooning. I tried my best to help, but it’s not like I had a lot.

Thanks to God, my brother successfully recovered, and other than the scar on the back on the base of his and the fact he has to sleep sideways and doesn’t seem to remember much of the past up until after the surgery, he’s ok.

I got him a special edition Nintendo 3DS and a bunch of games he wanted. I was able to smuggle these with the help of the wife of the Surinamese ambassador to Caracas, who helped me send these and some dollars since she had diplomatic immunity.

As for the feud between my mom’s brothers, the wheelchair-bound one that had lost everything, because he had nothing to lose at that point, essentially did a “deal with the devil” with some regime officials, and was able to recover control of the basketball team and its assets, for a cost…

Be that as it may, he was a man of honor, and the first thing he did was to pay for my brother’s medical debts, all of it. It was his way to thank my mom for the support, and because they were family.

Like the tale of the person who suggested I’d broker peace with my dad, the tale of that basketball team is long enough to warrant its own separate entry.

The rest of the year was business as usual, Chávez’s cancer was the topmost topic. Suriname finally got the urea, and the propaganda machine remained well-oiled and operational.

In 2012, an alarming trend among Venezuelan fishermen was the center of a controversy in Suriname. Throughout the year at least four Venezuelan vessels were caught illegally fishing in Surinamese waters. Although they would never admit to the fact, it was pretty obvious that the illegally-caught fish was sold through parallel markets and in foreign currency, a rather lucrative yet risky venture, as selling foreign currency in the black market was and still is profitable due to the regime’s controls on foreign exchange.

The first two vessels were let go with a warning after the embassy interceded. The third one took some convincing, but the fourth one? That was a headache and a half.

The vessel, named “Don Leandro” was caught redhanded with a noticeable amount of fish. The fishermen were arrested and although the embassy talked its way into releasing them, the boat was seized by local authorities. Now, I don’t know who those rather unremarkable men knew back in Venezuela, but after a few months of back and forth they somehow were able to get the socialist regime to wire them the $32,000 they needed to pay for the vessel’s bail — which, in my opinion, wasn’t worth a fraction of that.

The men complained that stuff was missing from the vessel, to which my aunt told him to suck it up because there was no more room for barnaging.

Because the world is indeed a small world, on the day we had to assist them in taking back the vessel, we had the help of a local Filipino fisherman that spoke Spanish quite fluently. He’d always travel to Venezuela for personal reasons, and he was one of my most recurring yearly visa renewal applicants. He tagged along and helped us talk with the local authorities on that dock because we were kinda lost that day and he said it was his turn to help.

Another growing trend was that of Venezuelans arrested for drug trafficking. There were several quiet cases, some of which predated my arrival to the country. The lengthiest case that I can recall was this group of four “fishermen” that got caught not with an illegal cargo of fish, but transporting several kilograms of cocaine. They kept denying any wrongdoing, saying that they had no idea the cocaine was there, I kid you not.

Another peculiar case was that of a man also arrested on drug trafficking charges, but whose Venezuelan identity card number did not match the country’s public records. In another case, there was this group of two men of African origins, with very much African-sounding names, who spoke English, but who had Venezuelan passports.

Other than the fact that they reminded everyone that they were Venezuelans every five minutes or so, everything else checked out — that is until one of them got arrested on drug trafficking charges shortly before I left, so I have no idea what happened to him in particular.

The regime finally modernized the visa system in 2012 with a new online platform that had a lot more features, such as reporting Venezuelans for criminal behavior — which was extremely tempting for my younger-self, I must say, other than the fact that it’d get my aunt in trouble.

They also sent someone to set up a new website for the embassy that followed their new unified standards. As a funny anecdote, she tried to go out one night and saw a frog pass by her as she left the hotel, which scared her so much she called my aunt for help, who said “don’t worry, you get used to it.”

The old server that hadn’t been installed since 2009 was finally put to work as a network and file server, giving some “modernity” to the otherwise outdated embassy which still majorly ran on Windows XP computers. Since I knew some of the people that set it up, the computer at my office was able to download torrents, so I committed some real international piracy during those days, because I left downloading stuff over the weekend using Surinamese internet under Venezuelan diplomatic territory. On Mondays, I’d plug an external hard drive and get my downloaded stuff out of that computer. I got a bunch of games, tv series, and other media with no one noticing what was up.

Other “modernization” stuff that the regime did during 2012 was sending the hardware for the new passports, which didn’t get installed at the time because the local ISP refused to allow the required ports to be free. The regime also peddled their own Linux Distro called “Canaima” and demanded that all public offices “decolonized” themselves from Windows. That distro was utterly garbage, and no one ended up bothering complying with that.

2012 was also the year that Suriname pledged itself to ALBA and the year in which the socialist regime passed its gun control laws under the grounds that it would curb violence in the country, but you know what the real goal of gun control is for a regime.

It’s also worth mentioning that in order to “curb down violence,” Venezuela passed a law in 2010 banning the sale of “violent” video games and toys, forcing people to sell games like God of War III under pseudonyms such as “The Baldy’s Game” or “God of Love”

Venezuela, collapsing as it was, had to prepare for the 2012 presidential elections. Chávez was up for reelection again thanks to the 2009 constitutional amendment that eliminated term limits. Chávez, who never disclosed what type of cancer he had, hid the severity of it and presented himself as a candidate as if he was healthy.

The opposition instead presented Henrique Capriles Radonski, a former governor now-turned regime collaborator, as its candidate. That year’s election took place in October 2012 instead of its usual early December. There was no official justification for this other than the fact that Chávez was dying, and they had to secure his reelection while he still drew breath.

Chávez won and the regime kept the charade going while they prepared for the inevitable post-Chávez future. Chávez appointed Maduro as his new Vice President, so in the event of his death, he’d become interim president until snap elections took place.

Everyone in the regime was in a “every man for himself” mode back in Caracas, and started to secure new positions for themselves. A lot of diplomatic positions were “renewed,” with the regime rewarding its people. Suriname finally got a new designated ambassador, so it was time to pack it up for my aunt.

The new ambassador, which did not arrive until April 2013, was an old lady whose merits was that she was Chávez’s secretary back in the 90s and her daughter was in cahoots with someone very close to the new Foreign Minister.

As is customary in Venezuelan public administrative offices, when a new boss comes you know they’ll bring their own team, so you’re expected to be replaced soon with people that have the new boss’ trust. That meant that sooner or later, and largely due to the nepotism nature of how I got that job, I would have to return to Venezuela.

Hugo Chávez made his final public appearance on December 8, 2012, which the socialists in Venezuela now declared as the “Hugo Chávez Loyalty and Love Day.” In his speech, he basically was discretely saying his farewells and final instructions: to vote for Nicolás Maduro should something happen to him, effectively proclaiming the successor to his dictatorship.

It is largely believed that Chávez died in December 2012 and not in March 2013, and they just kept his death hidden to buy more time and get all of their affairs in order in the most blatantly illegal way possible. The opposition never contested it when the time was right, so it’s not like it matters now.

Nicolás Maduro announced Chávez’s death on March 5, 2013. At the time, I was taking a nap after playing World of Warcraft for a bit. I knew I’d have to resign soon, so it’s not like I cared for work anymore.

I got woken up, and don’t get me wrong, but we had a bit of rum and coke. If my aunt had any sympathy for the regime, it had died the moment she found out they used her and then discarded. The rest of the days were centered on having people go to the embassy to sign the condolence book, peddle more propaganda, and all that.

Chávez’s death, whether it was actually in December 2012 or March 2013, changed the political game in Venezuela. New snap elections took place within 30 days of his “official” death, and Maduro ran against Capriles.

Maduro “won” by a roughly 223,000 vote difference. The narrow “results” prompted nationwide protests because something was undoubtedly fishy about it. The problem, though, is that Capriles, despite initially contesting the results, defused the protests and even went as far as to suggest protesters played salsa music at Maduro’s inauguration day instead…

The new ambassador and new councilor arrived in Suriname in April of 2013 and we started our preparations towards returning to Venezuela. I hadn’t actually made use of three year’s worth of accumulated vacation days so as soon as my would-be replacement was properly setup I took all those vacation days at once, angering the new ambassador because by having my aunt singing the vacations before she took office, she effectively “left the embassy without one of its best assets.”

I rode those three months of paid vacation like a champ, aware that I’d return with my family as soon as my aunt’s transfer papers came in. I finally had some free time since 2009, which was spent in packing up our things, watching television, getting hooked into the George Zimmerman trial proceedings and other media guilty pleasures.

I came back to the office around July with a fresh haircut, since my slight long hair was a point of contention for the new boss, who kept confusing me with one of his nephews, much to my dismay.

Supposedly, that old lady had a reputation for frisking her former female employees and other unsavory work ethics. Things were very tense, especially between my aunt and the new ambassador.

My aunt’s transfer papers finally arrived during a September 2013 Friday, a relief at last, from an awfully tense six months of waiting. I knew that was my last day working at the embassy. It’s a bit embarrassing but the last thing I did was to do number two on the bathroom, not out of malice, but because I really had to go.

I wrote my resignation and had it translated to Dutch over the weekend. On the following Monday I went very early to a Surinamese Labor Ministry office to have it signed, and then I waited outside of the embassy, which was still closed, to leave my resignation at whoever arrived first, seeing as the new ambassador and councillor were never on time. I went back home, and turned off my phone.

I went back to the embassy a few days later to say my farewells and to refuse an offer to stay, I had enough of it. Now, I eventually found out that the socialist regime was months away from implementing a new policy for all local personnel staff in all embassies, especially those with indeterminate labor contracts such as Suriname.

The new policy called for a complete renewal of all work contracts, and to make them last one year, renewable every year. Just like with the RCTV playbook from 2007, the idea was to not “fire” people but instead, “not renew your contract.”

That was the ambassador’s plan for me, I later found out, seeing as a few people there were subjected to that fate. I ended up dodging a bullet.

We packed out things, shipped what we could back to Venezuela such as my computer and other items, and I hopped on a plane back to the “Fatherland of Bolívar and Chávez” on October 11, 2013.

I am not proud of the time I worked as a cogwheel in the regime’s grand machine, even though it helped me with my social issues and I gained a few writing skills here and there among other things. I’m sure that there were or still are many similar cogwheels in not just Venezuela, but in other regimes throughout history as well